RULES AND EXCEPTIONS OF HEGEMONIC STRUCTURES OF LANGUAGE

by Garcia Frankowski

The Purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world—view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc, but to make all other modes of thought impossible.

-George Orwell, The Principles of Newspeak

I

Utopia could only be possible in a place where everybody agrees on the definition of the word ‘utopia’. In a state uniformly representing the same political apparatus, in which all flags wave to the same ideological wind. In such a place the notes of music, the space of architecture, the fabric of the city and the style of fashion will unanimously represent a unitary form of collective subjectivity. Utopia could only be possible in a total artistic dictatorship. A holistic mental choreography implies everybody following the same discourse. Everybody speaking the same words.

II

Newspeak is an utopian language. Orwell’s depiction of a plan for the control of the mind through the subtraction of ideas works like a mental barricade drawn out of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus to delimit the new limits of the world. Newspeak has been equals part Nazi and Communist, Fascist but also neoliberal Capitalism and radical avant-garde. Newspeak is Nihilistic Blackness, and red wedges beating the whites. Newspeak is institutional kitsch, parades, monuments and icons, but also commonplace aesthetics, and the banality of institutionalized ‘othernesses. Newspeak is the complete unobstructed rule of art over the everyday. Since the concept of utopia will be unimaginable in the linguistic kingdom of Newspeak, Newspeak implies that utopia will cease to exist. Newspeak proves that being defeats aspiration. To have no ambition is perhaps the final and definite stage of accomplishment. Newspeak melts utopia into air.

III

History is replete with attempts at imposing linguistic regimes. The ultimate form of socio-political cleansing and hegemonic control consists on the enforcement of this or that predetermined form of language. Like every political claim to power, every philosophical and artistic movement have announced—in more abstract or concrete terms— to have deciphered the definitive lexicon. Mayans and Egyptians implemented more or less successfully a rule of language controlled by artistic manifestations. Like them, spiritual regimes followed with the implementation of total art in the elimination of any form of difference and in the incorporation of resisting and potentially subversive elements in spoken, written, architectural, urban, visual and musical language. Sometimes loosely, other times with tight militaristic and economic grip, these regimes find consolidation through the use of absolute coercion and complete force. Newspeak can only be implemented in its totality. Half Newspeak is no Newspeak at all.

IV

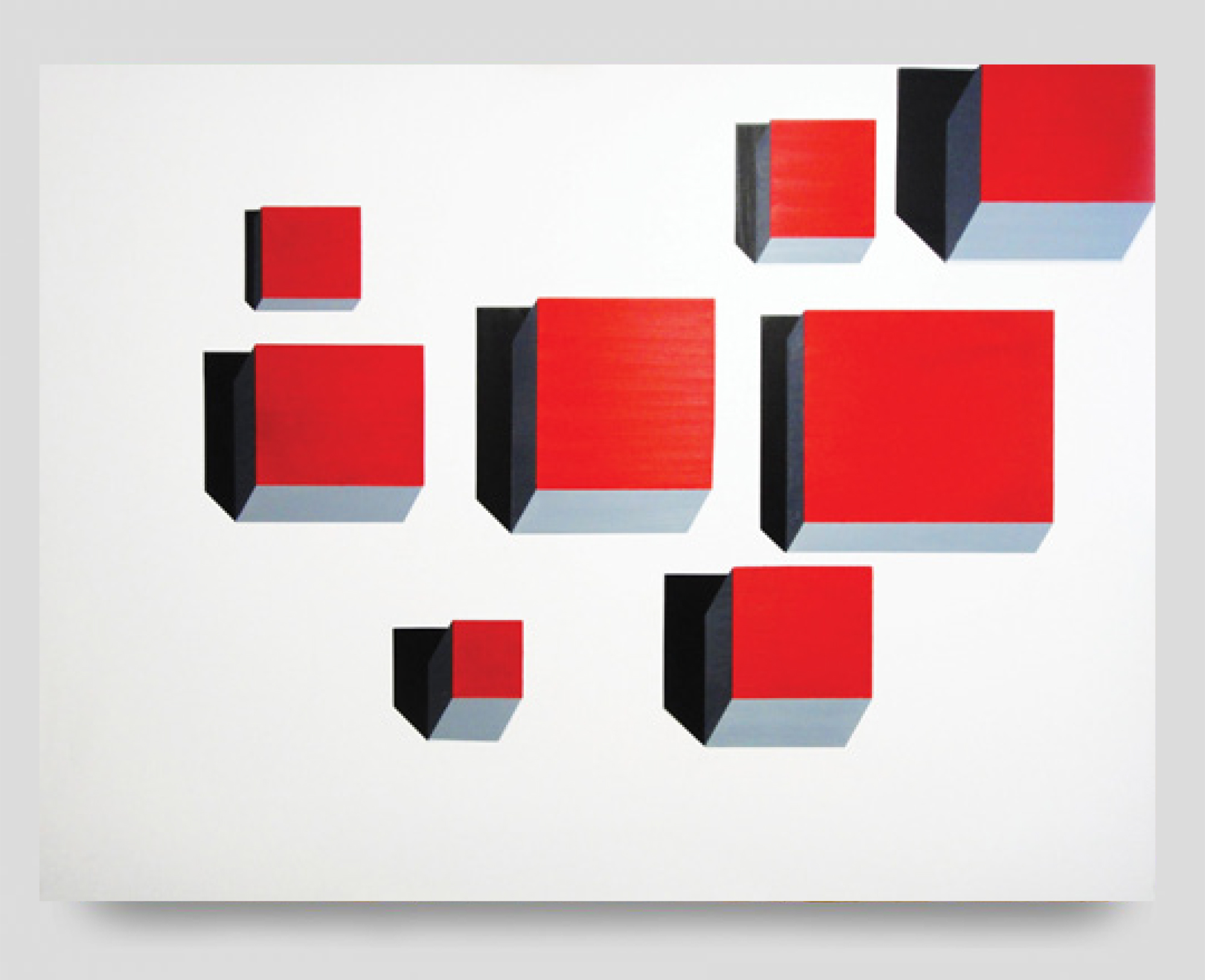

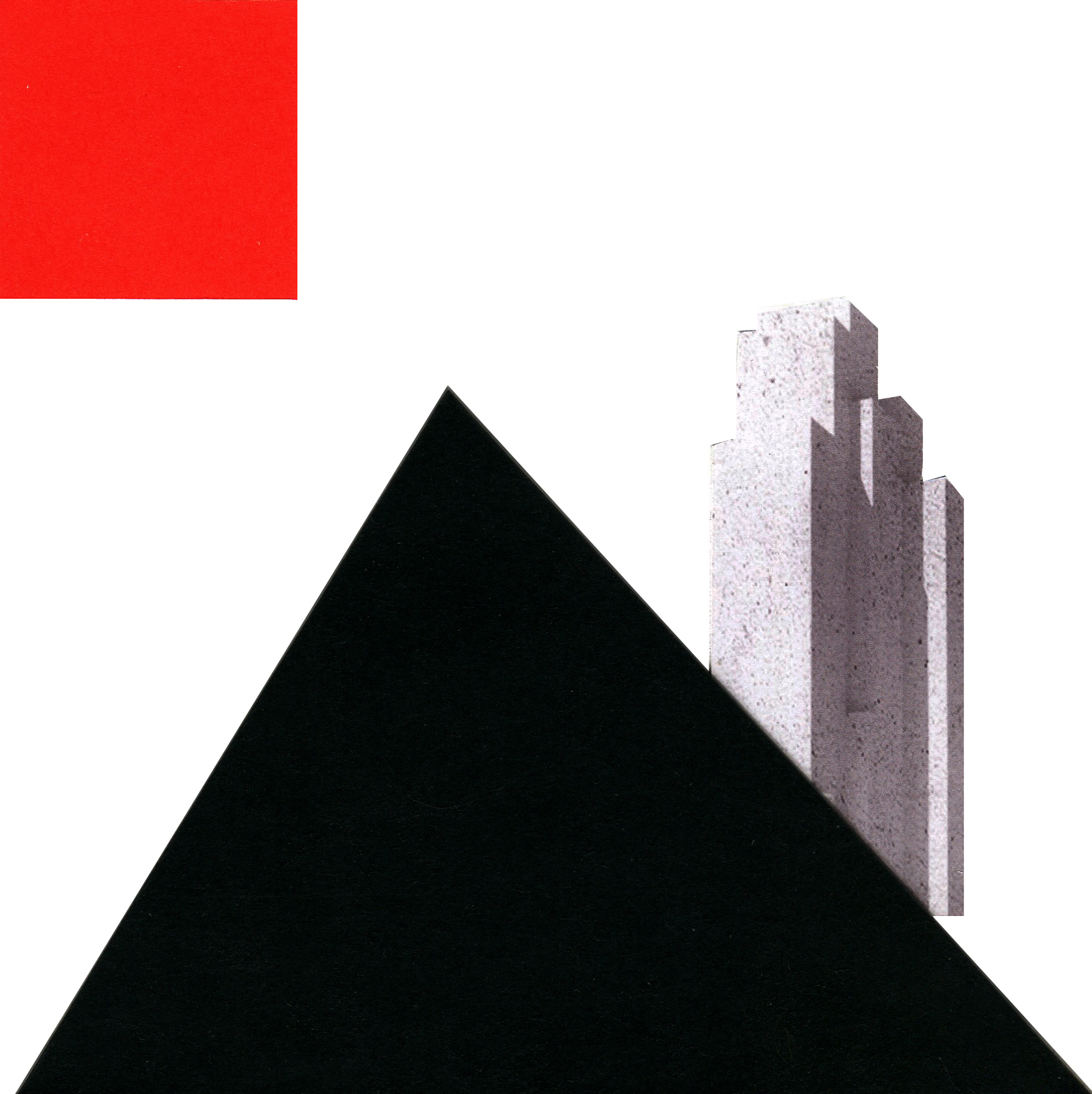

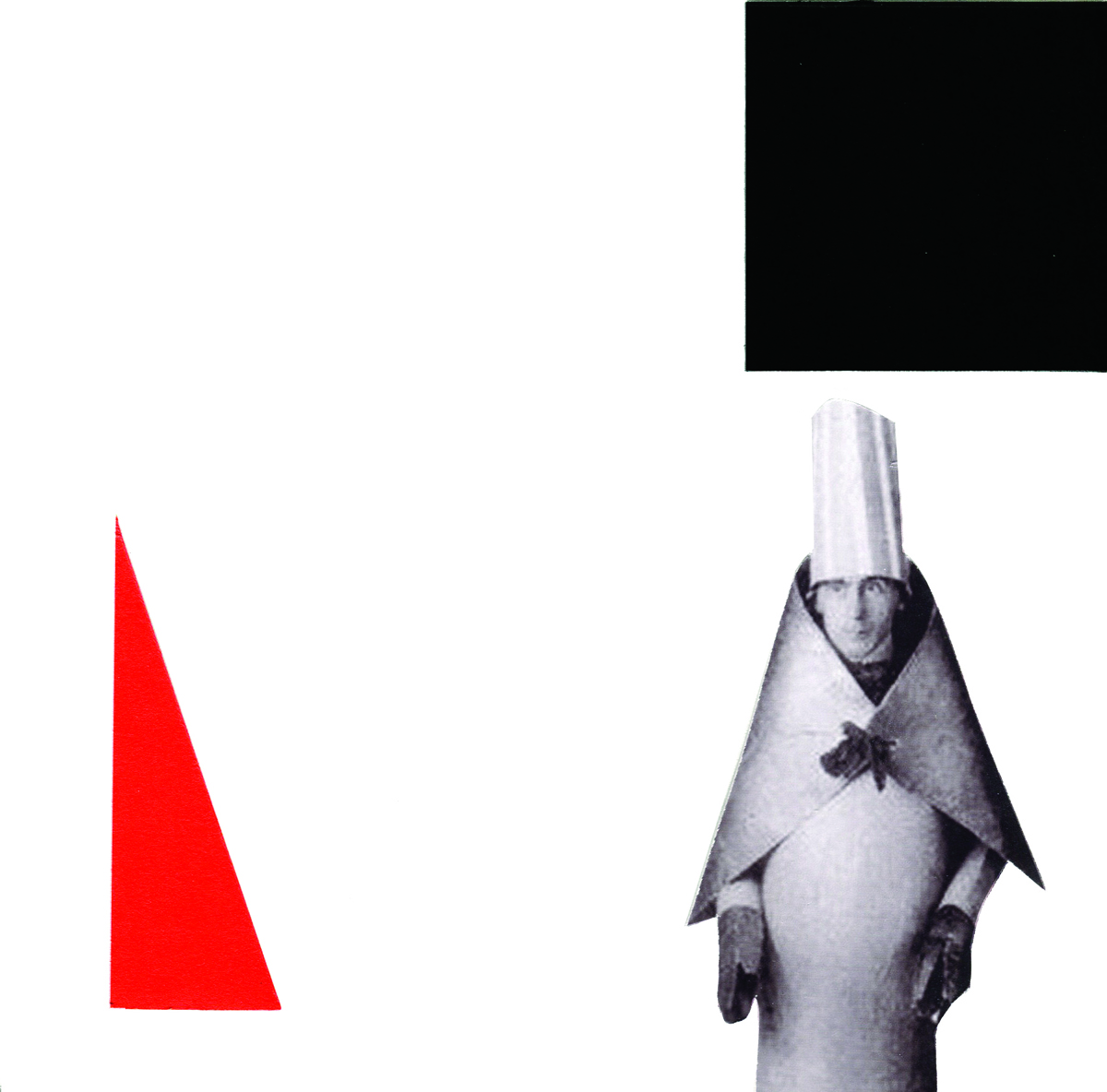

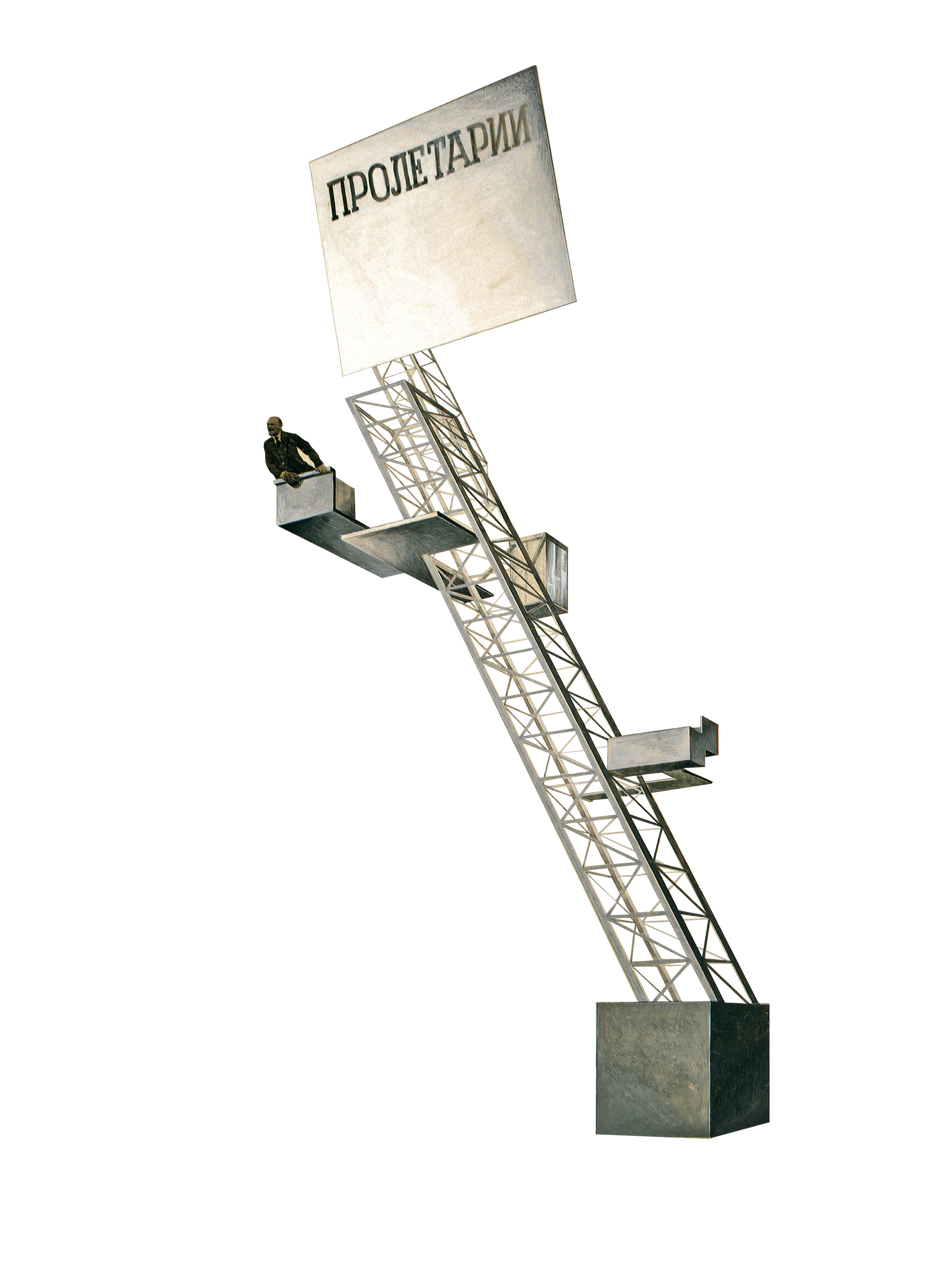

The 20th Century saw the birth, climax and collapse of several manifestations of Newspeak. With songs of cataclysm whistling in the air, in this period of total transformation art flirted with pure political power and politics used art to infiltrate in all spheres of life. Modernism with its unquenchable thirst for radical transformation, drove artistic projects to push humanity to the brink of complete obliteration. Abstraction and repetition became manifested as language reduction was tested and implemented. Methods, processes, footprints, plans, solutions, schools and circles became instruments of conceptual colonization. The avant-garde, a branch once thought to be isolated from mainstream political movements, found itself at the conceptual core of Fascism and the Bolshevik revolution. Black flags of nihilism and anarchism waved to the rhythm of imminent war. Either consciously or unintentionally, radical militancy and propagandistic paraphernalia ended up as blueprints of Newspeak. Ideological opposites found common resistance and mutual reverberation. Clashing ideologically, Malevich’s Non-objectivity and El Lissitzsky’s guide for socialist design found equal Stalinist objection and reciprocal acceptance as keywords of Hardcore Modernism. Modernism is Newspeak. Newspeak is the language of the commons.

V

Suprematism and Stalinism may not have been so contradictory after all. Both wanted to obliterate the actual world order. Both used language to create a new, ideal society. Both were radical transformations of the ruling world view. Black Square was an aberration, not unlike Socialist Realism. Like Stalin’s USSR, Nazi Germany also developed a similar strategy of total art as total war. Everything from the use of spoken and written German, to the slick uniforms, to the anthems of Wagner, and the plans of Speer worked as a series of codes for the final visual project: aesthetics as the ultimate sublime. Newspeak was pushed to new lengths. Just like Christianism was implemented with the enforcement of Spanish and Portuguese as official language in the Americas, Communism and Nazism flourished with the implementation of politics as a language.

VI

It would be tempting to stop the genealogy of Newspeak with the fall of the berlin wall. To declare the end of history as the end of Newspeak in a Fukuyamaesque rush of naïve nostalgia. However, it’s the advanced version of Newspeak that might be ruling today, not only in the blatant manifestations of a global network safeguarded by an industrial-military complex, but in the subtleties of a culture of the spectacle, marketing and advertisement. In the idealized lifestyle, and venerated pictures actively implemented and passively consumed. Global capitalism with its capacity to absorb, transform, mutate seems to have outpaced even its most averse resistance in the 20th century. By swallowing every image of contradiction in its insatiable vortex, Newnewspeak makes impossible the idea of exclusion. Newnewspeak is reduction as complete expansionism. Newnewspeak is a game of words and a serious consolidation of specific concepts that like political language can give an appearance of “solidity to pure wind”. Like doubleplusgood in the official reductionist lexicon, Newnewspeak makes emphasis on the ‘novelty’ of the new. Always evolving and in constant transformation, the cleansing of concepts in Newnewspeak never ends. With every position manifested and discourse developed, new forms of potential newspeak are created. Newnewspeak reflects on the artwork as reduction and as a critical reflection of the minimization of language. Newnewspeak is automatically updated with every project created, with every image, symbol, concept produced.

VII

Not only can Newnewspeak subsist as contradiction, it performs optimally in this state. Like the Newspeakean concept of Doublethink (a word employed meaning its absolute opposite achieved by the complete surrender of critical criteria), political art becomes the least political of the arts while terms like free, critical, and subversive are transformed into their complete antonym. Criticality floats in anesthetizing amniotic fluid, responding to opportunist scrutiny, while a new jargon of empty words –post-internet, post-humanist, non-profit, Chinese, African, South American, avant-garde, tropical, outsider, emerging—are employed loosely trying to include in the twofold operation of reduction as amplification, the positions (or lack thereof) and articulations of a broader economic infrastructure responding directly to the demands of capitalism.

VIII

Newnewspeak is a theory of the not-so-obvious political role of art as language, and the transformation of language as part of an ideological project. It explains the political use of non-political art, and describes how the tight grip of a ruthless regime employs art as language outlining concepts and perspectives by turning art once meant to be indifferent, subversive or, at least, free, into appendixes of its own ambitions and desires. Newnewspeak explains the ultimate reduction not only of art production, but of its narratives, discourses, systems into a codex of abstract propositions ready to enhance market transactions that like stocks rise and fall out of speculative value. When the market is everything and everywhere, Newnewspeak turns language reduction into a sales devise.

IX

The questions that remains is, if everything (images, lifestyles, positions, and critiques) could potentially be Newnewspeak, how can any position, discourse or work present a challenge or at least place a form of opposition to it. Because no system is perfect, Newnewspeak also faces a series of challenges. The total acceleration of its expansionist and reductive impulse could lead to the complete collapse of its supporting structures. When there’s nothing else to suppress, and nothing else can be absorbed, the system with its ideological superstructure and speculative-materialistic infrastructure will come to a halt; to the ultimate stop. A loss of momentum will lead to its contraction, and eventually to its collapse. Like a star that burned itself into a black hole, accelerationism will only lead to the ultimate deceleration. The final victory of Newnewspeak will imply its own demise.

X

Against the acceleration of reduction, the only remaining hope will be to operate fueled by detachment, neutrality; meaninglessness and absurdity. Under the volatile nature of subversion, irony and provocation, art can aim to withstand one ultimate battle in front of hegemonic discourses that look to inject specific meaning behind Newnewspeak and infiltrate with it every aspect of life. To remain detached from an ever consuming idea of ideas and its set implications, to dig deep into the unconscious and avoid looking for answers; to speculate on the perversity of narratives, geopolitical stances, aesthetic codes and accepted social roles, to battle against the tradition of the old and the tradition of the need to pretend to be new, to laugh in front of the seriousness of political correctness and established discourses, is today perhaps the ultimate form of idealism.

It might take continuous exercises of extreme futility. We could end up waking up inside fictional dreams, launching mental Molotovs against walls of orthodox brick, lying a simulated death in front of the systemic tanks, walking barefoot in a field of ideological landmines, becoming invisible in a laser field, or we could take a Diogenesian piss against the ideological wind to detach ourselves from the omnipresent orthodoxy of Newnewspeak.

There is a chance that this form of naive idealism might provide with the only way out (if only momentarily) of Newnewspeak under its current circumstances. And, if what’s going to take to resist the unbearable pull of Newnewspeak is to create a new form of Newnewspeak, then we will have to be ready to articulate unrecognizable gibberish because when nobody can understand what’s being said, it would be impossible for all to agree on the definition of the word utopia.

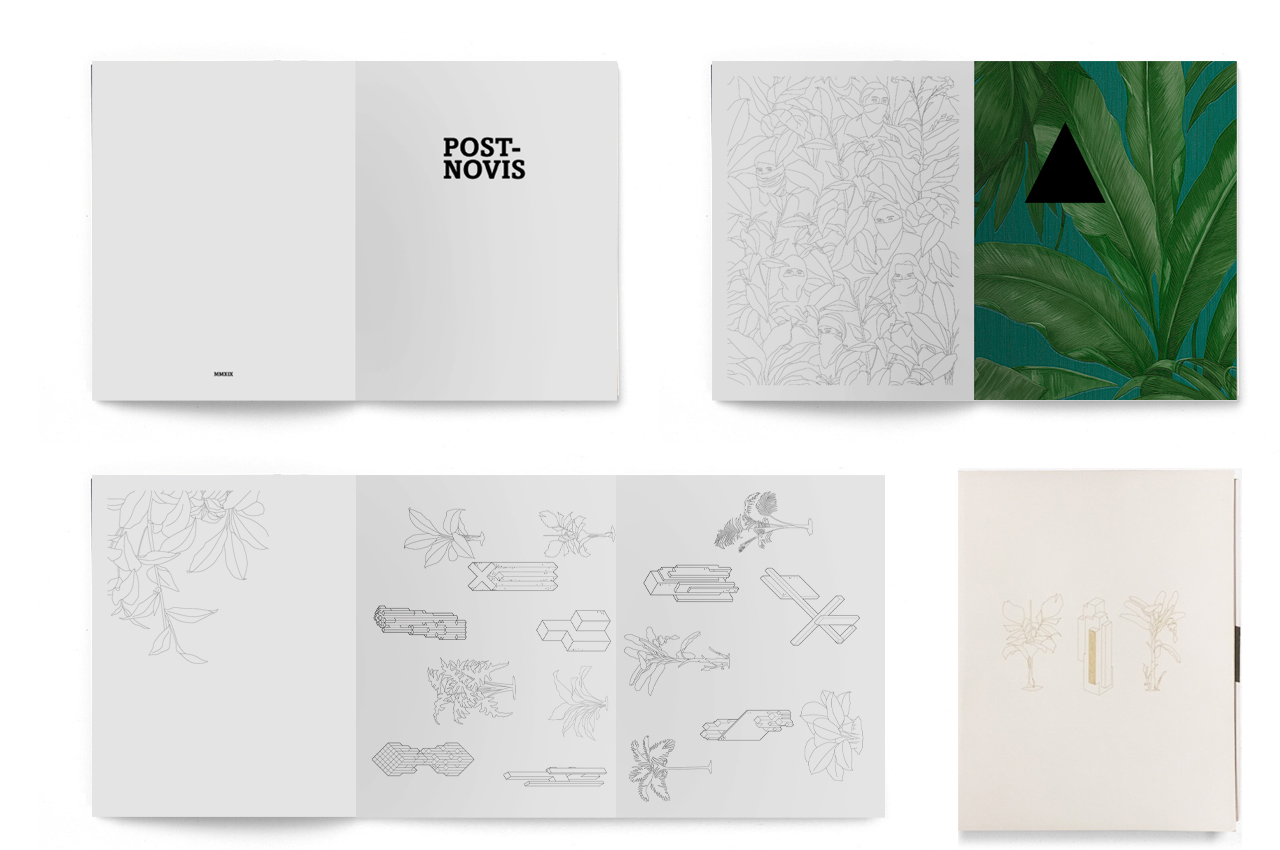

Text published on the occasion of Newnewspeak exhibition.

MEMORY MONUMENTS, MASTERING MATTER

Garcia Frankowski

Monumento, memento, monstrum. Memory manufactures motifs. Motifs mold memories. Multiple memories make more monuments, museums, myths. Monuments morph museums. Museums make myths. Myths modify minced memories. Memories morph material myths making megaliths, messianic mirages, Manichean machines. Materialism mobilizes masses, motivating misinterpreted missions. Marcel mastered members modestly made, mirroring masterfully Malevich’s minimalist militant mutiny. Mindless misreading makes messages misinterpreted memories. Material matter multiplies. Matching mass, memory motivates making more. Making more masters memory, makes material monuments, masters manufacturing matter.

Text published on the occasion of What is Matter? Exhibition

MATTER EXPERIENCE

Garcia Frankowski

No social order ever disappears before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have been developed; and new higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society itself.

Therefore, mankind always sets itself only such tasks as it can solve; since looking at the matter more closely, we always find that the task itself arises only when the material conditions necessary for its solution already exist, or are at least in the process of formation

–Karl Marx, The Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

Everything flows and nothing stays.

–Heraclitus

I

Nothing exists without matter, not even experience.

The more we contemplate the relationship between these two apparently distant concepts the more we end up with the conclusion that matter and experience cannot be disassociated from each other.

After watching how our lives and environments (political, social, and geographical) are affected, shaped, transformed by matter, a set of ultimate answers looms clear: There is no matter without experience. There’s no human experience without matter.

II

Through the materialist lens, ideology gains only power when experience is at stake.

The act of living is always seen in relationship to the inherent properties of matter, including that which is living, and that which is not.

Human beings and inanimate objects are in constant movement (in constant exchange) because of the forces that shape matter and sets them on a continuous struggling motion that transforms matter and our experience with it.

Everything is submitted to the forces of matter.

All matter is submitted to the subjectivity of experience.

‘What is Matter’, ‘what is Experience’ are two questions directly related to each other.

This exhibition presents works that reveal the experience of matter, and present matter as experience.

III

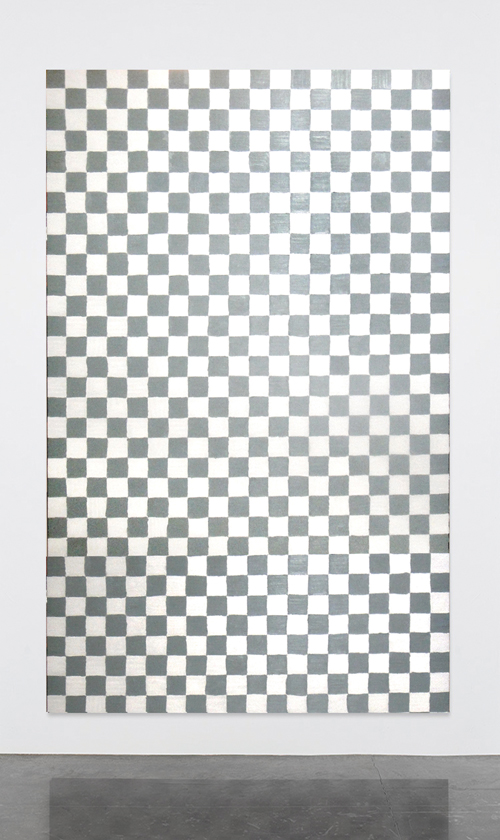

Wang Guangle paints matter and experience and matter as experience.

His Coffin Paint is simultaneously a conceptual act in the form of time-based art production, and a physical act, as it takes the idea of transforming matter (the coffin that has been painted throughout a life) to transform more matter (the canvas in which the painting has been applied on).

The act of painting as process carries the potential of art as experience, not only for the public gaze but for the author that ritualistically brushstrokes the canvas with acrylic paint, applying layer after layer, colour after colour.

Painting acts as a recording device in which accumulation of paint marks the time that has been consumed in the production of the art project. Matter and experience also reflect a socio-cultural construct, the idea of the death of the body that is projected in the act of giving life to a coffin that will contain the deceased machine once the body has stopped to work, therefore prolonging the desired experience of the body once experience has technically stopped happening.

The canvas records in the act of painting the ideological makeup that accompanies it and also projects the desire of a future experience that aspires to transcend our material world through the development of matter and experience.

IV

A series of virtual “minerals” float inside the invisible amniotic fluid of the empty vacuum of monitor screens. They breathe, move, transform. Ada Sokol’s abstract tridimensional mineral pieces suggest matter as transformation, matter that breathes, matter as a living organism that inhabits the invisible circuits, assemblages, pieces, networks that are fueled with real minerals that have been extracted, transformed, modified from the earth in order to create the technology that is used to render and display them.

The invisible flows of matter extraction, development and consumption is manifested in this virtual minerals, small matter that are just appendixes of colossal structures that keep our world of experiences in constanct motion.

V

For Serge Attukwei Clottey the current state of matter exchange is presented through a form of performative critique. The political aspect of matter production and consumption, of the global economy of matter is used as the object of his Social Sculptures.

By turning the ubiquitous yellow gallon (used as a market controlling device) into a performative mask, the material is recycled, repurposed and up to a point, weaponized, turned into an objectile, both projectile and object, as it identifies the object of criticism and turns it into a multidirectional ballistic critique.

The commonplace object is identified as an ideological device and transformed into a matter-machine. The yellow gallon is not anymore just a yellow gallon, but an instrument of discourse deconstruction, and a door opening to a world of events, of experience fueled by a critique of the flows of matter and the ideology developed with them.

VI

In a city often stricken by environmental discussions associated with air quality (coal playing a significant role on this issue) the act of using “problematic” matter to create functionless beauty allows to contemplate the potential afterlife of a material whose functionality, and purpose seems to be the source of many challenges.

In a way anachronistic, coal fuels lives in this city but also has the potential to deteriorate them. Here, coal controls our experience of modern life and affects the flows and networks of society, politics and economy. Coal is presented as the problem when in reality is just a mere vehicle through which the dialectic keeps moving.

Jeff Miller and Thomas Schmidt’s ‘Recycled China’ series repurposes the problematic material into the object of their sculptures. Constructing in a form of ‘action painting’ a hybrid of coal and aluminum, the experience of dripping aluminum and coal generates a deep reflection on the modes and methods of matter consumption, fulfilling our critical and aesthetic demands while putting in motion a form of resistance to the utilitarian exploitation of matter in detriment of our lives.

VII

Everything flows, and nothing stays the same. Creating a form of experience matter, and deploying a hybrid matter experience shows how matter (however singular or apparently isolated) is an event that carries, provokes and stimulates experiences. Every work in this exhibition presents matter as experience and experience as matter, from the coffin paint carrying matter as history and potentiality, to the floating abstract minerals of virtual aesthetics, to the repurposed yellow masks turned into ideological war-machines to the re-use of coal pieces turned into sculpture-painting . Nothing exist without matter, not even experience. Nothing exist without experience, not even matter. Nothing exists without matter and experience, certainly not this exhibition.

Text published on the occasion of What is Matter? Exhibition

Ten Points on the Sublime Object

by Garcia Frankowski

1

The sublime is formless. Its formlessness displays in its discontinuous properties an intrinsic dialectical nature.

2

In the Kantian dynamic and mathematic sense of superiority, the sublime performs reciprocally between our understanding of that which we find in nature as being understood and comprehended, and that which goes beyond or under the rubric of reason, the laws of logic and structure of values.

3

When Wittgenstein affirmed that a logical picture of facts is a thought because in a proposition a thought finds an expression that can be perceived by the senses, he concluded that the general form of a proposition is: This is how things stand. Since the Sublime is formless, the Sublime is an anti-proposition, the Sublime stands in a no-place.

4

Once the possibility of empirical recognition is established, and objects, experiences and phenomena are subsumed under the grip of our ontological power of denomination, the sublime disappears. The formlessness of the anti-proposition is transformed in figures with logico-pictorial form. On the contrary, the potential of awe and fear, admiration and terror in front of the unknown in contrast to evidence, facts and given assumptions creates space for the Sublime Object’s anti-propositional pictures.

5

The disambiguation of a concept implies a forced landing in territory of reason, while the sublime object clears the lane for takeoff beyond the grasp of any theory of comprehension. The Sublime Object presents the pursuit of searching as praxis, as object and objective are anchored in territories beyond the limits of our judgment in relation of the faculties of our imagination and our understanding.

6

The Sublime Object presents both propositions and anti-propositions in order to highlight by way of the understood that which stands in defiance of the structure of reason.

7

For every object as picture in common with what it depicts, there’s an object devoid of logico-pictorial form. The Sublime Object lies in the fulcrum of this dichotomy creating a composition of propositions and anti-propositions, between objective and non-objective.

8

A Composition of anti-propositions is a proposition in the form of a thought-picture in the same way that the composition exists as a non-picture of the world and occupies the non-territory beyond its limits. The non-objectivity of anti-propositions allows sequential objects to be read in non-sequential narratives. It creates a non-objectivity of objects.

9

The Sublime is in the picture and in the object of the picture when the picture lacks logico-pictorial form. Non-objectivity can be found in the picture as the unintelligible language of the picture. When language goes beyond the limits of the world, it becomes anti-language since its symbols are devoid of thought figures and its pictures don’t deliver any logico-pictorial form.

10

The object of the Sublime consists on creating pictures of the formless and restructuring the world by means of anti-logic, by constructing reasonless anti-propositional pictures. The object of the sublime lies in its non-objectivity both as anti-object in its concrete, logico-pictorial form and in its lack of definite objective.

Ten Points on the Works in the Sublime Object

by Garcia Frankowski

1

The Works in the Sublime Object deal with both the Sublime and the dialectic of its Object and objective.

2

The Works in the Sublime Object are arranged in a dialectical relationship to each other, to the viewer and to the space that contains them. Overall, the resulting installation of the Sublime Object is compositional in its non-proposition, and propositional in its compositional thought picture.

3

The Pictures in the Sublime Object, both static and moving are simultaneously propositions and anti-propositions. They deal with the Sublime and with logic in their autonomy and in the collective subjectivity of their relationship to each other, the viewer and the space that contains them.

4

The Pictures in the Sublime object are both, propositional in their thought-picture capacities, and non-propositional in their non-logico-pictorial performance.

5

The Paintings and artifacts in the Sublime Object deal with logico-pictorial issues but also with formless values. Ideas, concepts and motifs stand with and against each other, reacting to one another and remaining autonomously indifferent.

6

A Picture of a picture is not necessarily a picture as thought figure. A group of formless pictures could form a logico-pictorial picture. In the installation a group of thought figures develops into the formlessness of the Sublime Object.

7

The Sublime Object is experienced in a dialectical environment created with a composition of propositional logico-pictorial thought figures, and non-propositional pictures. The combinations in this composition of propositional logico-pictorial figures and non-propositional forms are boundless and can be found as follows: logico-pictorial proposition→ non-objective figure; logico-pictorial proposition ← non-objective figure; logico-pictorial proposition → logico-pictorial proposition; non-objective figure → non-objective figure. In all its variations the combination can result in logico-pictorial propositions and as the Sublime object.

8

Not all sequences are narratives; nor they try to deliver the picture of a proposition. The Object can be the structure of the proposition. However, the Sublime Object is non-propositional in its structure and the multiple combinations of its compositional logico-pictorial figures and non-propositional forms are possible configurations of both propositions and the object of the Sublime .

9

Poetry is a composition structured with thought-figures. Poetry as anti-structure is sublime. The Sublime Object is poetry as structure in its compositional arrangement.

10

The Sublime Object is its own dialectic. It exists as both objective thought figures and anti-propositional non-objectivity.

Text published in the occasion of Newnewspeak exhibition.

FUNDAMENTAL COMRADES

by Garcia Frankowski

Like Comrades of Time, each of the artists reacts to circumstances of contemporary life and artistic production. Tacticians on a universal strategic game, they mediate, analyze, scrutinize the flows and networks of production, representation and diffusion –of ideas, images, concepts, products. They look outward into new worlds. Into the systems of multilateral exchange, into the advertisement of abstractions, and the wormholes that generate value via the connection of distant conceptual universes. They look into the commodity as art, and art as the commodity in a realm trapped between the rebirth of history and the decay of fragile ecosystems. They look inwards too, reflecting on the perennial questions of our existence. Once the cosmic ambitions have landed on newly discovered seas, they highlight with dark humour the ideological constructions that give or take meaning from the condition of being-in-the-world while floating in the metaphorical fluid of the desktop background. The computer screen, mirroring reflection of our hybridity as physical and virtual entities, shows the existential remains of an eternally pixelated shipwreck. Floating in these vast oceans some colonies have created mythologies concerning physiological avatars, and the psychological machines that fuel them. Meanwhile, others focus on the utilitarian commodity in its ideological and aesthetic function. At once cosmonauts of unknown digital galaxies, and sailors of these geopolitical seas, each artist confronts in the novelty of the medium and the legacy of discourses two facets of contemporary artistic production. In this pavilion of paradoxes, each comrade works with new media to answer old, fundamental questions.

For Pavilion of Comrades

MAP TO UTOPIA

Garcia Frankowski

Utopia is a state not an artists’ colony. 1

Utopias are sites with no real place. They are sites that have a general relation of direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces.2

Utopia is thus by definition an amateur activity in which personal opinions take the place of mechanical contraptions and the mind takes its satisfaction in the sheer operations of putting together new models of this or that perfect society.3

Yet with Baudelaire, in the ‘death-loving idyll’ of the city, there is decidedly a social, and modern, sub-stratum. The modern is a main stress in his poetry. As spleen he shatters the ideal (Splee et Ideal). But it is precisely the modern which always conjures up prehistory. That happens here through the ambiguity which is peculiar to the social relations and events of this epoch. Ambiguity is the figurative appearance of the dialectic, the law of the dialectic at a standstill. This standstill is Utopia, and the dialectical image therefore a dream-image. The commodity clearly provides such an image: as fetish. The arcades, which are both house and stars, provide such an image. And such an image is provided by the whore, who is seller and commodity in one. 4

So far as a society producing under capitalist conditions is concerned, the commodity has not become any cheaper, the new machine signifies no improvement. The capitalist is therefore not interested in the introduction of this new machine. And since its introduction would make his present and not yet worn-out machinery simply worthless, would make old iron of it, would mean a positive loss for him, he takes good care not to commit such a utopian mistake.5

What can undoubtedly be said is that the model of society proposed by William Morris certainly would not be utopian in a world where all men were like William Morris. 6

He called it “Utopia,” a Greek word which means “there is no such place.”7

Utopia leaps beyond time..., using means whose existence was determined from the beginning within a given reality, it desires to achieve a perfect society: paradise, a fantasy dependent on its time.8

Utopia was not built for those who exist. It was built for those who come later. In order to create the new man it was necessary to destroy the old. 9

Utopia has two fields of possible realization. 1. Existing power, whatever it is, assimilates the means, the criticisms, and the project of utopia, therefore, in a certain measure, its goals, by rejecting them. But, if there had not been a fundamental modification of the existing order, a share of utopia nevertheless passed into reactionary praxis. 2. The revolution that destroyed the topos theoretically permitted a total realization of utopia, which becomes a (revolutionary) topos. In advance, one cannot determine what will constitute the revolutionary praxis of this topos and what will remain theoretical and reintegrated in theory. The realized utopia is a new topos, which will provoke a new critique, then a new utopia. The installation of utopia passes through a (total) urbanism.

And that is the complete process.

Topos(conservative) —critique/utopia/revolution— urbanism / topos (revolutionary and conservative)/new utopia…etc. We call that Dialectical Utopia. Utopia is the phase of theoretical construction, but it is absolutely indissociable from the other planes and can only exist as part of dialectical utopia. It is only through dialectical utopia that we can elaborate, outside and within the present system, an urban thought.10

Above and beyond this one could perhaps say in general that the fulfillment of utopia consists largely only in a repetition of the continually same “today.”11

But I believe that we live not very far from the topos of utopia, as far the contents are concerned, and less far from utopia. At the very beginning Thomas More designated utopia as a place, an island in the distant South Seas. This designation underwent changes later so that it left space and entered time. Indeed, the utopians, especially those of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, transposed the wishland more into the future. In other words, there is a transformation of the topos from space into time. 12

In fact, when I think of the fair and sensible arrangements in Utopia, where things are run so efficiently with so few laws, and recognition for individual merit is combined with equal prosperity for all—when I compare Utopia with a great many capitalist countries which are always making new regulations, but could never be called well-regulated, where dozens of laws are passed every day, and yet there are still not enough to ensure that one can either earn, or keep, or safely identify one’s so-called private property—or why such an endless succession of never-ending lawsuits?—when I consider all this, I feel much more sympathy with Plato, and much less surprise at his refusal to legislate for a city that rejected egalitarian principles.13

Republics are very easy to found, and very difficult to maintain, while with monarchies it is exactly the reverse. If it is Utopian schemes that are wanted, I say this: the only solution of the problem would be a despotism of the wise and the noble, of the true aristocracy and the genuine nobility, brought about by the method of generation—that is, by the marriage of the noblest men with the cleverest and most intellectual women. This is my Utopia, my Republic of Plato. 14

The entire life of a nation—beyond the formal sum of individuals standing for themselves, that is to say, living and struggling for their land, their place, their Da-sein—carries within itself (concealed, revealed, or at least occasionally caught sight of) men who, before all loans, have debts, owe something to the neighbour, are responsible—chosen and unique—and in this responsibility want peace, justice, reason. Utopia!15

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias.16

One of the “proofs” of my practice of fetishist disavowal is the alleged “perverse paradox” of me rejecting utopias and then nonetheless claiming that today “it is more important than ever to hold this utopian place of the global alternative open” - as if I did not repeatedly elaborate different meanings of utopia: utopia as simple imaginary impossibility (the utopia of a perfected harmonious social order without antagonisms, the consumerist utopia of today’s capitalism), and utopia in the more radical sense of enacting what, within the framework of the existing social relations, appears as “impossible” - this second utopia is “a-topic” only with regard to these relations. Utopia as simple imaginary impossibility (the utopia of a perfected harmonious social order without antagonisms, the consumerist utopia of today’s capitalism), is not utopia in the more radical sense of enacting what, within the framework of the existing social relations, appears as “impossible” - this second utopia is “a-topic” only with regard to these relations.17

We must therefore admit that the refusal to legitimize murder forces us to reconsider our notion of utopia. In that regard, it seems possible to say the following: utopia is that which is in contradiction with reality. From this point of view, it would be completely utopian to want people to stop killing people. This would be absolute utopia. It is a much lesser degree of utopia, however, to ask that murder no longer be legitimized. What is more, the Marxist and capitalist ideologies, both of which are based on the idea of progress and both of which are convinced that application of their principles must inevitably lead to social equilibrium, are utopias of a much greater degree. Beyond that, they are even now exacting a heavy price from us. 18

“Now,” he said to me, “you are going to see something you have never seen before.”

He carefully handed me a copy of More’s Utopia, the volume printed in Basel in 1518; some pages and illustrations were missing.

It was not without some smugness that I replied: “It is a printed book. I have more than two thousand at home, though they are not as old or as valuable.”

I read the title aloud.

The man laughed.

“No one can read two thousand books. In the four hundred years I have lived, I’ve not read more than half a dozen. And in any case, it is not the reading that matters, but the re-reading.

Printing, which is now forbidden, was one of the worst evils of mankind, for it tended to multiply unnecessary texts to a dizzying degree.”19

The language of the Image-repertoire would be precisely the utopia of language: an entirely original, paradisiac language, the language of Adam -- “natural, free of distortion or illusion, limpid mirror of our sense, a sensual language (die sensualische Sprache)”: “In the sensual language, all minds converse together, they need no other language, for this is the language of nature.20

The poverty of a civilization which, avowedly destroying every kind of constrained to the most practical the basest necessities, those of the mechanical and industrial type! The poverty of a period that replaces divine luxury of architecture, the highest crystallization of the material liberty of intelligence, by “engineering”, the most degrading product of necessity! The poverty of a period which has replaced the unique liberty of faith by the tyranny of monetary utopias!... 21

All efforts to describe permanent happiness, on the other hand, have been failures. Utopias (incidentally the coined word Utopia doesn’t mean ‘a good place’, it means merely a ‘non-existent place’) have been common in literature of the past three or four hundred years but the ‘favourable’ ones are invariably unappetising, and usually lacking in vitality as well. (...)

Nearly all creators of Utopia have resembled the man who has toothache, and therefore thinks happiness consists in not having toothache.22

“That’s it, Fukada was supposedly looking for a utopia in the Takashima system,” the professor said with a frown. “But utopias don’t exist, of course, anywhere in the world. Like alchemy or perpetual motion. What Takashima is doing, if you ask me, is making mindless robots. 23

The search for Nirvana, like the search for Utopia or the end of history or the classless society, is ultimately a futile and dangerous one. It involves, if it does not necessitate, the sleep of reason. There is no escape from anxiety and struggle.24

All utopias are depressing because they leave no room for chance, for difference, for the ‘miscellaneous’. Everything has been set in order and order reigns. Behind every utopia there is always some great taxonomic design: a place for each thing and each thing in its place.25

Life in More’s Utopia, as well as in most others, would be intolerably dull. Diversity is essential to happiness, and in Utopia there is hardly any. This is a defect in all planned social Systems, actual as well as imaginary. 26

If Communism is Utopia it is indescribable because Utopia, being no-place, cannot have any definite form. Every attempt to describe Communism necessarily functions as a projection of the personal prejudices, phobias and obsessions of the writer or artist who tries to undertake such description.27

I would like to say (perhaps as a final thought), what conclusion can be drawn from this exhibition or even from this conversation. You could say this. While mankind still lives, each of us produces a utopia. Creating projects is as natural to man as the discharge of secretions. People always fantasise. We make plans, programmes, compose something or other. But when the plans are implemented in reality, especially by those in power, who have climbed quite high up the ladder of power, all these projects end in catastrophe, blood, destruction or chaos. This produces a terrifying arc: projects are inevitably devised, but inevitably end in failure and death. The question arises: what to do with these projective and productive components? The answer is: divert them, channel them into special ‘utopia-receivers’. Maybe build a ‘Museum of utopias’, or many such museums.28

Text for the exhibition Not a State, but an Artists' Colony

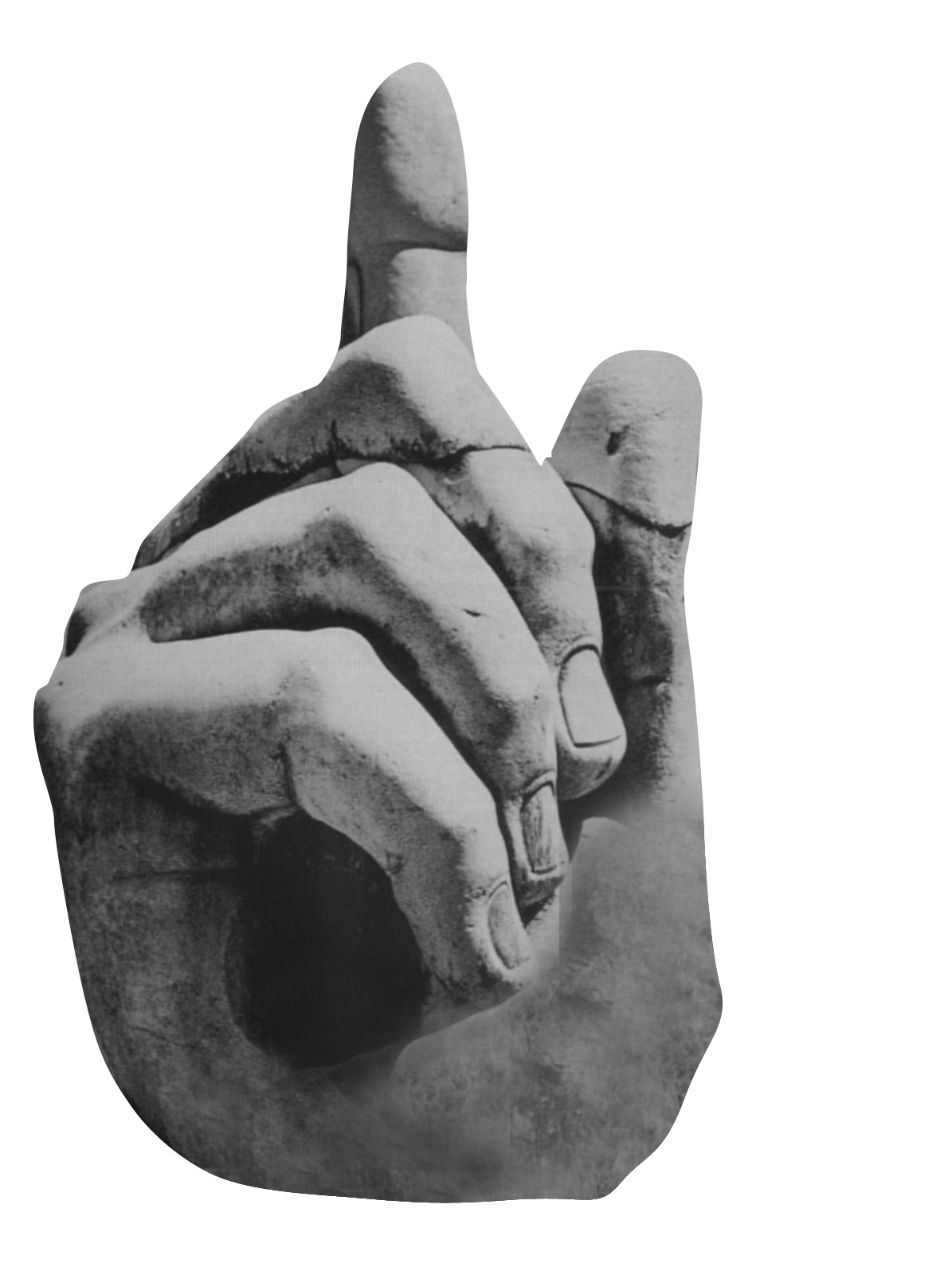

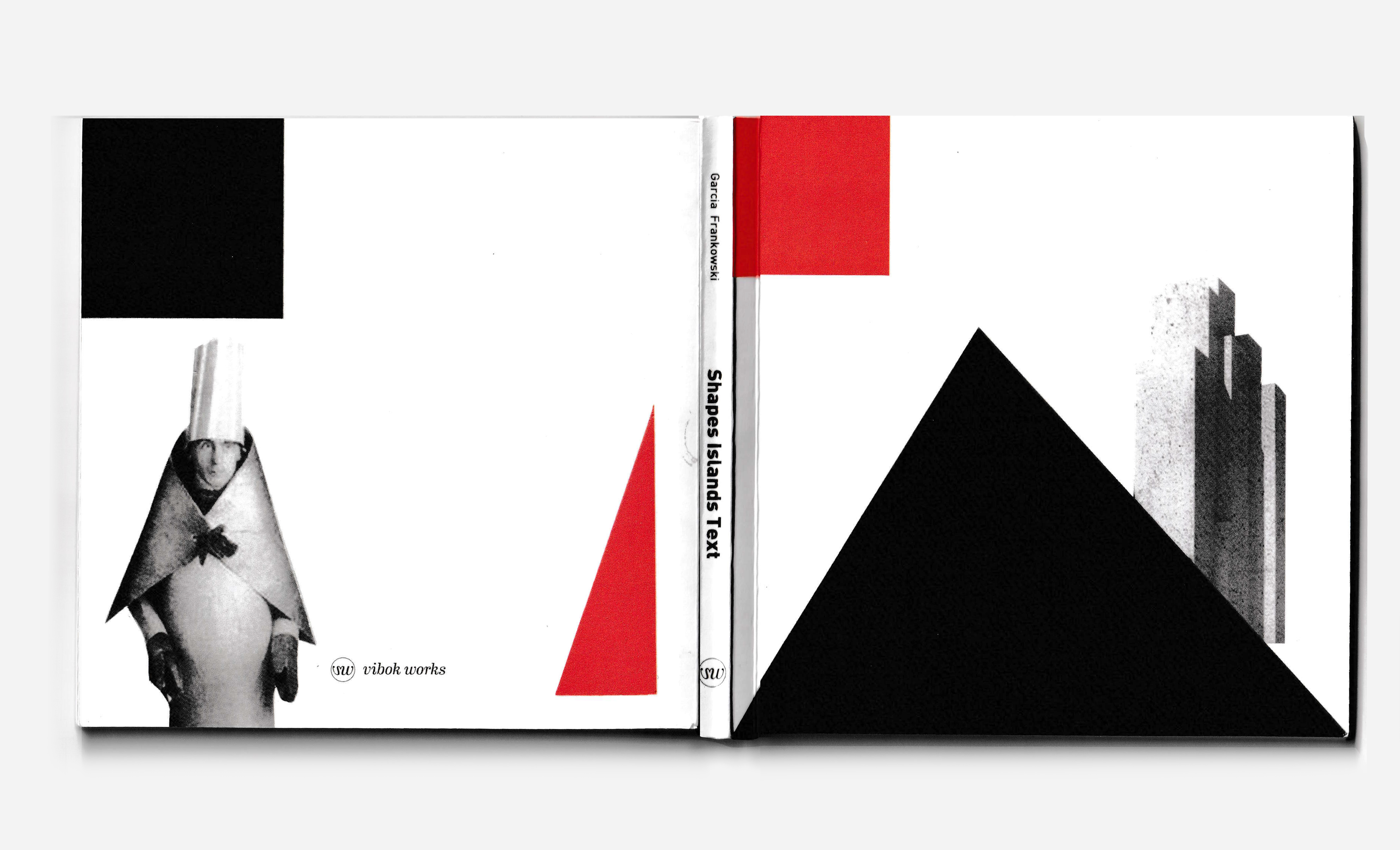

SHAPES, LADDERS AND CONCRETE BUTTERFLIES

Garcia Frankowski

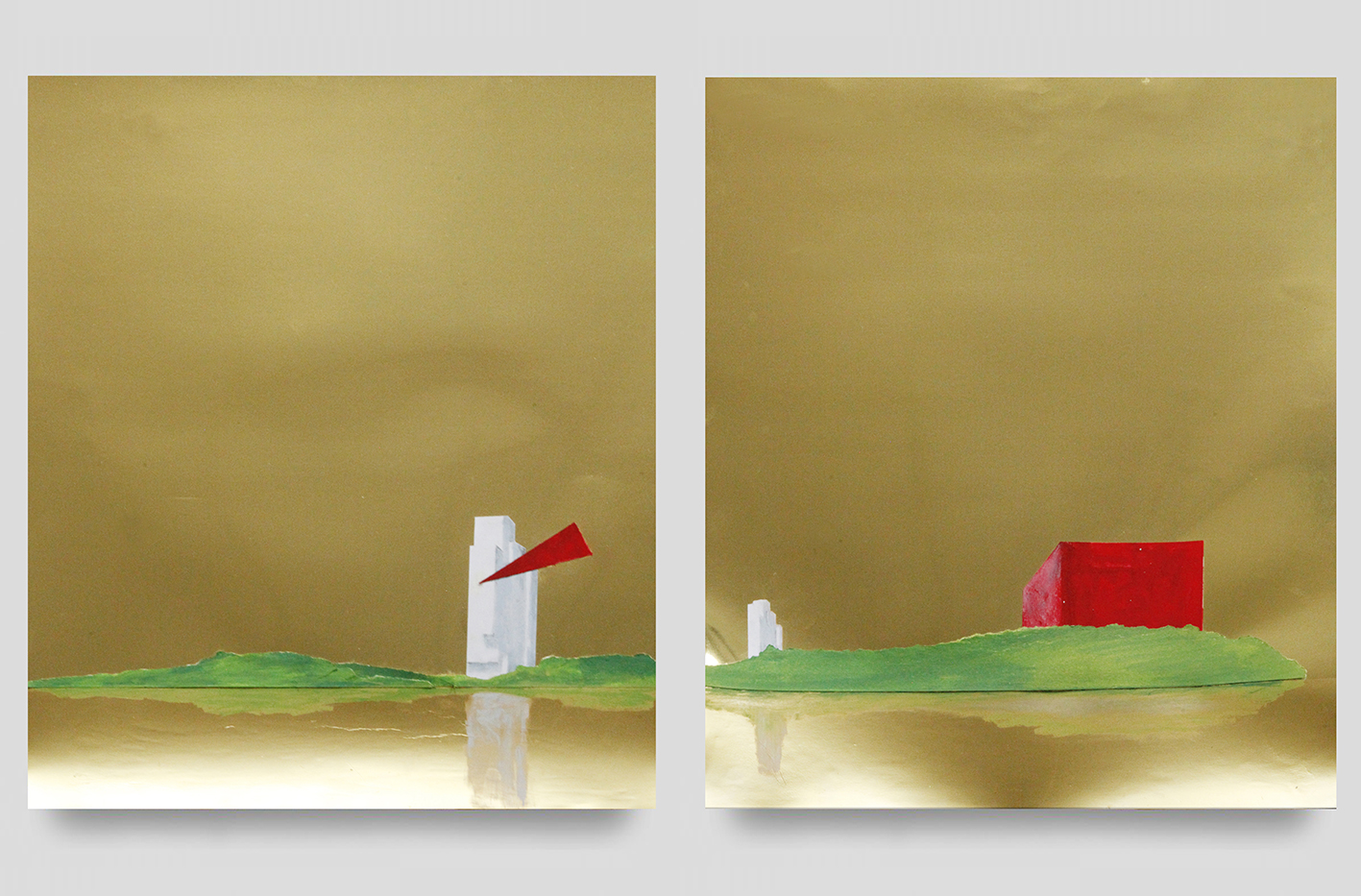

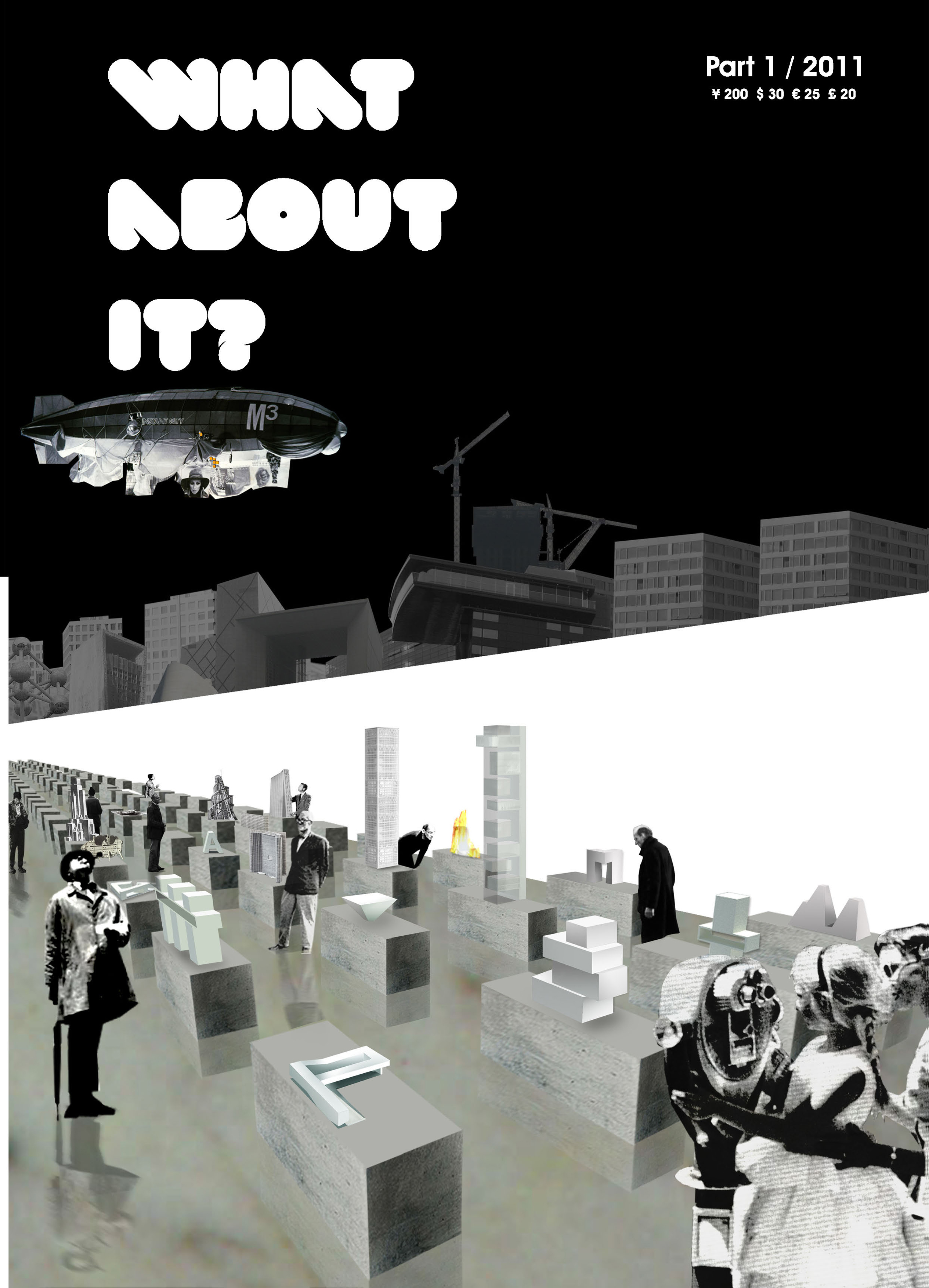

This exhibition is about Utopia, or better said, about blueprints, fragments, dreams, indifferent aspirations, celebrated and unknown failures of utopian ideas.

Since it doesn’t have a single definition, Utopia is said to be several things at once.

Utopia can be found in the (im)perfect shapes and (in)complete missions.

It can be pursued as intentional goal, or as involuntary tradition.

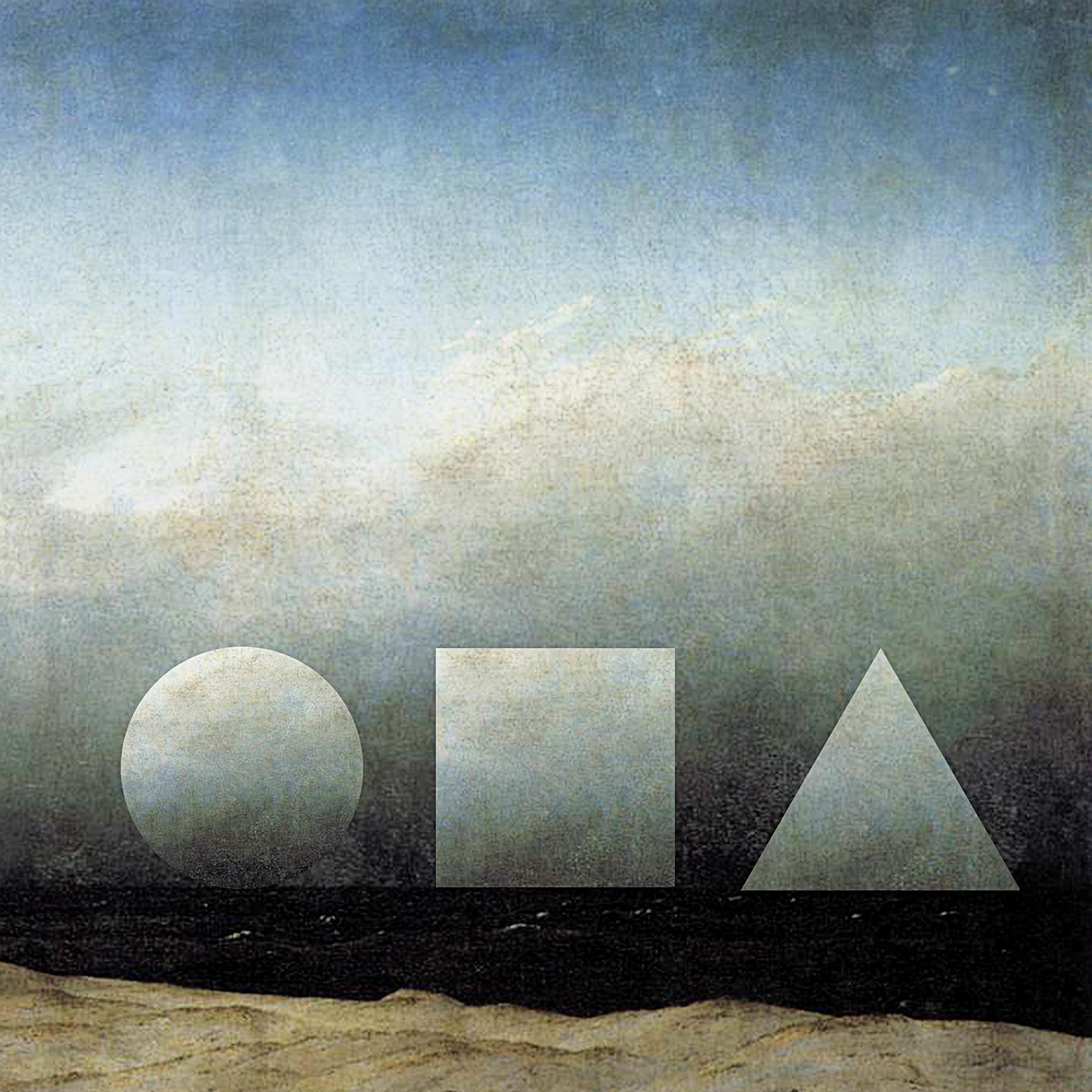

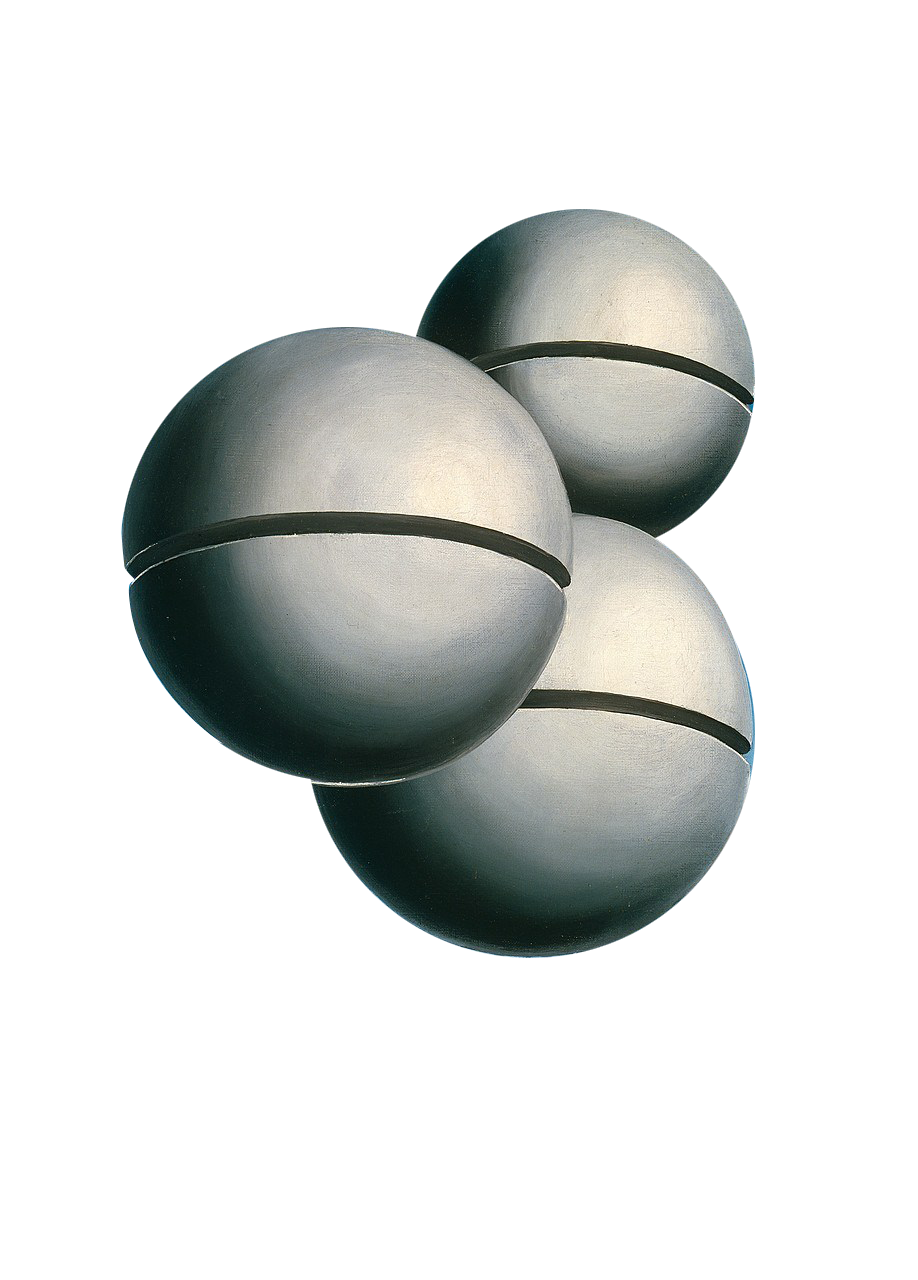

Utopia can be discovered in platonic shapes effortlessly meeting in Euclidean compositions, as if suggesting sublime forms of historical relevance. A square turned into a circle, a corner piece bringing walls together, a sphere decoding space in its own mirrored interpretation, are all fragments of an ongoing utopian project of geometry.

Geometry focuses on formal manifestations of utopia. Pure shapes occupy post-humanist territories.

Every attempt to reclaim geometry, is an effort to bring back fragments from utopian worlds.

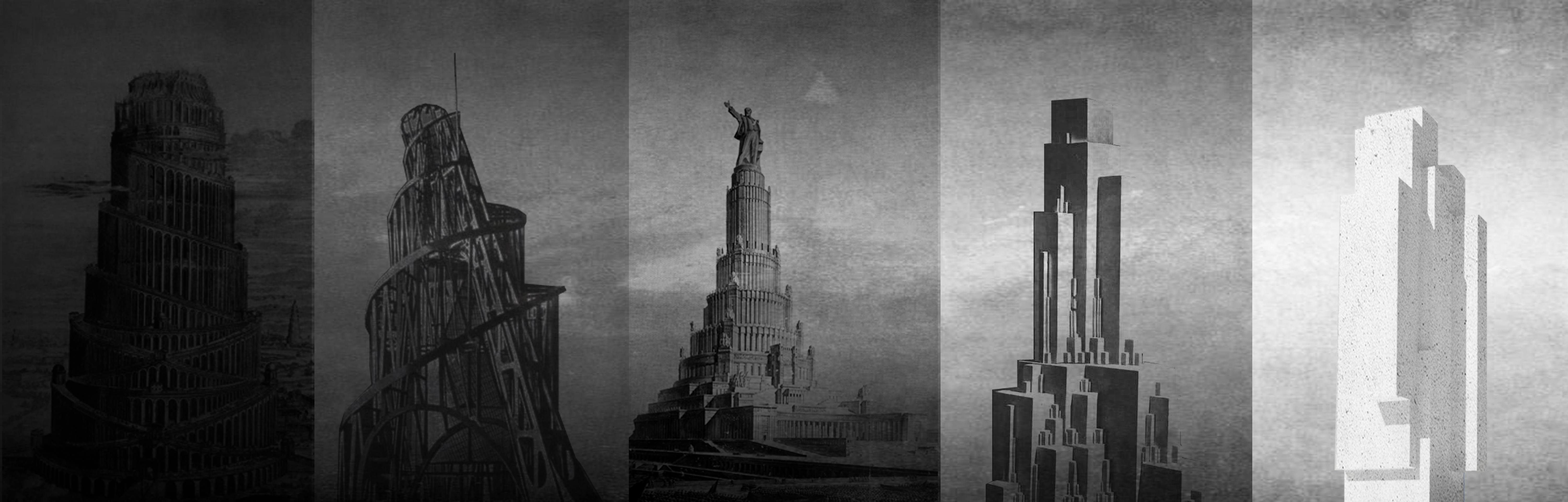

In history, Utopia can be seen on the spoiled wings of stranded concrete butterflies. Always trying to take flight. Always stuck to the ground, unable to lift the unbearable lightness of all solids that melt into air.

Concrete can’t fly. Utopian concrete is doomed to fail. Like the palace crashing down. Like the kingdom of the proletariat. Like a platonic shape unable to reach its pure perfection. Like the utopias of the 20th century.

Utopia is said to be also at the end Jacob’s ladder. An archetype of mythical proportions. Each step closer to utopia. Each step itself utopian. It promised to open up a clear view to a dreamscape. Flawless, beyond our current imperfections.

For every dreamscape, there’s a soundscape. Sounds travel in utopian waves. Minimalist anthems, songs of utopia.

Music orchestrates utopian experiences through blueprints and notes. In the form of spheres, that like the mirror ball, reverberate inside the body, occupying the impossibility of interior space, liberating experience from any physical context. Utopia is phenomenological. Metaphysical. Utopia is complete unachievable human experience. Spiritual embellishment. Impossibility in disguise.

Utopian colonies inhabit contrasting territories. From the ruin of the unknown on the scale of personal ambition, to the still standing muscular monuments and effigies of collectivized leaping ambition. A small unfinished structure that displays the scars of fleeting time in abandonment is the other face of the monumental coin of the Ostalgic. Concrete is utopia. So it’s a broken sphere, music in the air, steps leading nowhere, a leap into the infinite.

Text for the exhibition Not a State, but an Artists' Colony

THE YELLOW ONES ARE FOR THE ARTIST

Curatorial Observations of Five Conceptual Approaches

by Garcia Frankowski

The work of the curator consists of placing artworks in the exhibition space. This is what differentiates the curator from the artist, as the artist has the privilege to exhibit objects which have not already been elevated to the status of artworks. –Boris Groys, The Curator as Iconoclast

A man goes through the task of separating a conglomerate of balloons into yellow and colored ones. Once all the yellow ones have been grouped together, he proceeds to cover the remaining balloons with yellow paint.

Conceptual appropriation is the magic trick of contemporary art. Take this or that object, paint it yellow, make it yours. Painting the balloons is what differentiates the artist from the curator. The curator can show the balloons the artist has painted. The artist has the power to paint them. Unlike the curator who only has the capacity to show works of art, the artist possesses the alchemistic gift to transform, to make all the colour balloons, so to speak, yellow.

With ‘the yellow ones are mine’ Elsie Yi Shen sheds light on a fundamental issue about the understanding of contemporary art, and how it is presented, exhibited, understood. Not only does the artists wants the balloons to be hers, she wants the balloons to be yellow too.

The art project consists in fitting and developing narratives, concepts, arguments and forms that respond to the aesthetic requirements of the artist. Sometimes the artists sets form-based rules. Sometimes the aim is shifted towards process. Zhang Xuerui’s blueprint consists on a juxtaposition of these two concepts. Laying out a set of Cartesian guidelines, a meticulous grid reveals a gradient of shapes and hues. If the balloons were seized by the violence of the painting act, painting is now employed through mathematical compositions and combinations of triangles and quadrilaterals swiftly oscillating from yellow tones, to turquoise and fuchsia. The man sequestering the balloons has been substituted for an almost automated time-based process in which the production of the artwork is as important as the experience of the viewer when confronted with its visual structures.

Like the canvas and the balloons, bodies, commonplace objects and phrases are part of the archaeological territory to be excavated by the artist. Sonia & Mark Whitesnow work with transformations in the domain of the human body. Their repertoire consists of body features, through the lens of fashion photography and the multiple array of tools for their manipulation. ‘Regina Hair’ displays an alteration of the female body through digital filters and effects. The work addresses in its explicit fictitiousness the role of computer manipulation of the female body, an issue critical for understanding the language of mass media and advertising. The work questions our relationship with representations of the body using as framework the rules in which fashion and cosmetic institutions harvest the ideology behind desired aesthetic values. A naked body washed in floods of milky light exposes how digital manipulation deals with issues related to the body, gender and sexuality while simultaneously challenging the idea of photography as a tool for legitimate and accurate anatomical depiction.

Engel Leonardo and Jade Townsend’s works prioritize on the power of reclamation by ways of reinterpretation of commonplace objects in the first, and conceptual phrases in the second. For Leonardo vernacular architecture elements are referenced in Feijacun 1 and Feijacun 2, as two objects—fence and pedestal—are recreated in abstract geometrical manifestations. A circle-fence and a pyramidal pedestal bring the visual experience of his context into the exhibition space. The fence, the element of separation is stripped of its original capacity and is instead turned into a wall object, a sculpture of sorts, while the pedestal works as an installation redirecting the view from the object to the environment in which it has been situated.

In similar fashion, Townsend presents 进化 (JinHua/Evolution) in bold letters. The metal LED display plays around catch phrases and slogans, of the propaganda used by advertising to sell products, lifestyles, and vague ideas. The multiple meanings of 进化 that go from evolution to progress, advancement and growth take the reader to the field of political language, where the power of concepts and their representation is exacerbated through the manipulation of its thought figures. In the context of making art, narratives are started by ambiguous readings that like colour balloons are left to be painted. The exhibition reflects on the polyvalent dimension in which art is created by reclamation, appropriation, manipulation, reinterpretation, by bringing items of common life to the exhibition space, highlighting the unreachable ambitions of computer aided manipulations of the corporeal, setting blueprints for processes and outcomes, and underlying phrases that either evolving or progressing, leads us to the ultimate conquest by claiming ‘the yellow ones are mine.’

Text for the exhibition The Yellow Ones are Mine

NEVER ENDING STORIES

Garcia Frankowski

Modernism is a fantasy. A twisted fantasy. Always drawing to a grand finale, Modernism finds life in the idea that the end is always closer. Modernism implies breaking and reorganizing rules, restructuring life. Playing with history while trying to erase it simultaneously. Like a dystopian piece of science fiction, Modernism is feared to produce future cataclysmic events, often as the byproduct of the interaction of people with the technology they develop. In Modern life everything becomes a machine. The city is a machine. The Home is a Machine. The Economy is a Machine. The government is a machine. The machine is a machine. But, what if instead of trying to disassociate people from the machines they create, this exhibition would offer the point of view from these machines as a sci-fi novel with five different chapters? What if these machines would be telling a story? Every image possesses the ultimate potential of being a projection of the ambitions, desires, fears, criticisms and fantasies of modernism. A first chapter of this epic would start by approaching the idea that modernism is a human creation.

The visionary imagines and engineers the blueprints of mighty machines. Before setting up to take over life, the machines exist not as objects, but as atmospheres in the mind. They exist as psychological landscapes on paper. They exist as abstract annotations of a developing project. While Chen Xi lays down the foundations of a robotic future, jagged edges and twisted metal unfold in material form on the walls of the gallery.

Wang Sishun installs two sheets of lead thus exposing the toxic material as both, reminder of failed ambitions, and of the still ongoing project of modernization. This second chapter goes from the expanding fractals of the machines on paper, to an indeterminate boundless of metal sheets. Either spare scraps of a failed construction, or pieces for a possible future structure, ‘Indeterminate Boundless’ brings the abstract concept of modernist fantasy to its material stage. Are these parts of the machines of the future or wreckages of projects past? Isn’t modernism like these metal pieces, in apparent state of decay but always holding new promises?

The third chapter and fourth chapter reaffirm that the fantasy exist as visual bait. The utopia is always reachable due to its chameleonic character. Due to its visual appeal. Sometimes the idealistic dream of modernism is transformed into muscle cars with the promise of a suburban utopia.

The car is often the door to a twisted fantasy of individuality, of horizontality, and freedom. If Camille Ayme ‘Inglewood’ car and spinning wheel are images of the suburban machine, Xiao Xiao presents its counterpart with the modernist apartment as an urban machine. ‘Rational Reality’ exposes the hygienic minimalism underlying the urban ambition of inhabitation. Its windows loom not so much into the city that surrounds them, but inside the psychological reflection that projects the urban desire of personal space in the apartment as a machine for living. The image is then processed and constructed in a way as to become almost as abstract as the machinistic blueprints in the first chapter of the story. With the frightening potential of the lead panels hung on the walls. The city, the metropolis as a concrete concentration of wealth in the form of skyscrapers offers the apartment as the only available cells inside the modernist organism. For those who claimed that modernism failed, it takes seconds to realize that abstraction and repetition are tools used by the capitalist machine not only for weaving the fabric of the modernist city, but for drawing the bucolic scenarios of the suburban landscapes of contemporary urban sprawl that serves as the city’s supposed antithesis. If the Muscle car is the suburban machine par excellence, the epitome of the urban condition is the apartment cell as machine.

This leads us to the fifth a final chapter (or the first) of this story in which the creation of value, the consolidation of the ideology that supports it and the materialization of these as abstract structures of power is presented in the ‘Confusion of Tongues’ by Jason Mena. By stacking coins of Latin American countries in a reference to the Babel Tower an anticlimax is reached.

Never before has been the modernist fantasy so twisted as passing through five chapters that go from desire, to materialization, ambition, fear, and ultimately the possibility of collapse of an ambitions project that provokes the possibility of drawing new blueprints and start imagining and building machines all over again.

Text published in the occasion of Twisted Modernist Fantasies

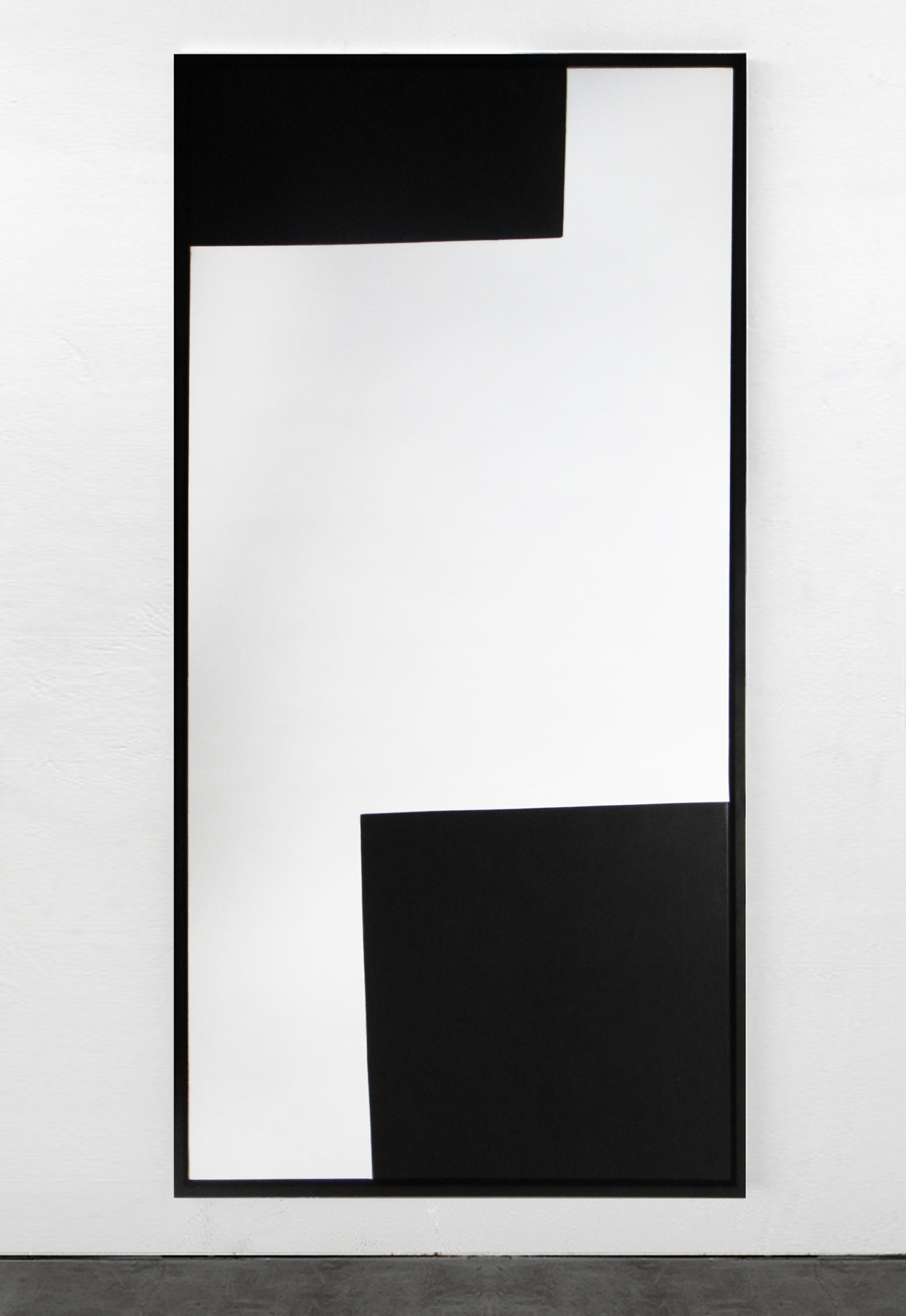

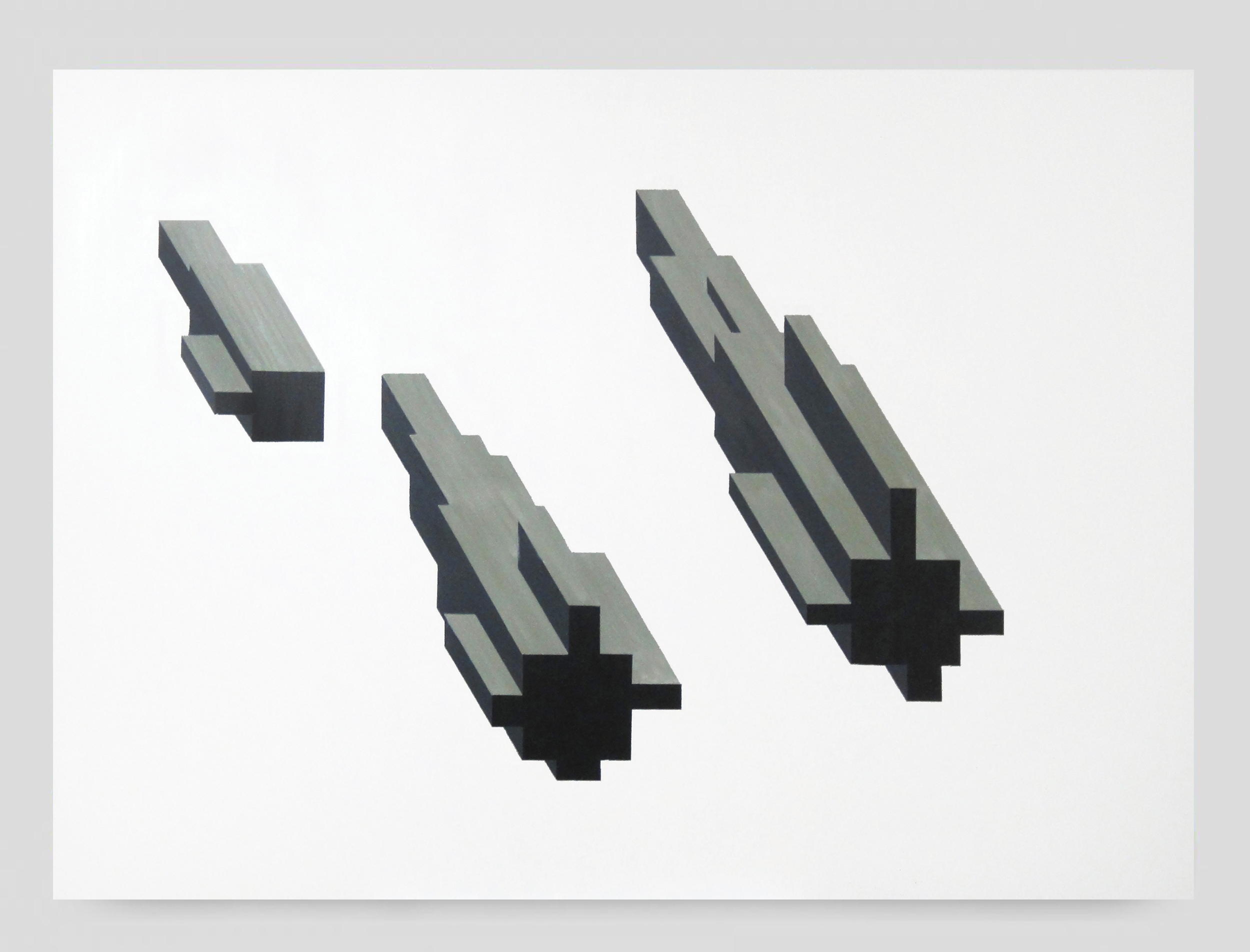

ENUNCIATING NOTHINGNESS

Indifferent. The Black Square went from reflecting upon the world, to creating its own world. Radical obliteration led to a complete denial of all previous attempts at reducing, abstracting, synthetizing ‘something’. The Black Square marked the beginning of an end, and an end as a new beginning. Its urgent, imperfect surface was the blueprint of nothingness. With it, nothingness was graspable, within reach. The Black Square was nothingness as a project of aesthetic self-representation.

Like Duchamp, Malevich was a solipsist militant leading a nihilistic mutiny. Black Square and readymade (both concepts born in 1915) were weapons for an epistemological coup d’état anchored in absurdist foundations. By the time the metaphorical fireplace transformed into a bicycle wheel started spinning on top of a wooden bar stool (1913), the nonsensical ‘кошелек вытащили в трамвае’ (c. 1914), ‘Purse Snatch in Streetcar’ or ‘The Wallet was Stolen in the Tram’, was allegorically framed inside the almighty square.

The Black Square, like the absurdist phrase, or the quotidian ‘object of complete indifference as far as aesthetics are concerned’—to put it on Duchamp terms—were rebellious acts against the world order, the world previously depicted, represented, portrayed, and summoned by art. Both devices were a new grammar for a new way of understanding.

A hundred years later we’re left with the possibility of working on the aftermath of a victory over nothingness. Inside this rhetorical void, ideas, concepts and energy clash as works implode concepts of abstraction, pictorial representation, or even the purely aesthetic attitude easily sequestered into the polarization of the superstructural manifestation of the current socio-political-economic apparatus.

Nothingness challenges the role of art as politico-aesthetic advertisement. Philosophical reflexes find material concretization in a realm beyond contextual narratives or temporary trends, working on the nothingness left by the theoretical collapse of preconceptions and assumptions of the profane and commonplace.

Nothingness represents the most radical stance in a world where something has become the fleeting, flickering image of everything. It stands against a world where political stances are absorbed into their opposite, producing an ever expanding grammar of opportunism, a lexicon of populist ontological dimensions. A Victory Over Nothingness presents Nothingness as a total finality. It presents the possibility of works as post-critical praxis; Nothingness as dynamic Gesamkunstwerk, art as a total work of Nothingness.

--

In its role as post-linguistic apparatus and as total work of art Nothingness can be perceived both in the artwork itself and in the process of creating the artwork. This process is something that has characterized Xie Molin’s practice in recent years. Although previous exhibitions have drawn a picture of his work as ongoing exploration of procedural hybridity, these experiments of art-making, and conceptualization can be traced back to a nirvana, a defining moment in search for nothingness.

Line Study No. 3 marks a departure within a departure. Developed by means of readapting a cutting plotter into a painting machine, the work belongs to the first series of pieces created using repetition of a process without pictorial representation as reference. The method instead creates a new vocabulary, a new form of concept as rhetoric. The work ventures into a space composed of colour, patterns, surfaces and textures. The machine is no longer used to translate references from reality; the machine is no longer a channel to drive an image into a work of art. Representation is substituted by self-representation. Process takes the place that inspiration or derivation usually occupies. Landscapes, and narratives disappear into gradients and atmospheres. The image disseminates into a vast array of unidirectional lines, moving horizontally through the paper surface.

By utilizing the machine as collaborator to create art, no longer the question is posed over the role and possibilities of the artwork, but it’s the artist who is challenged. Line Study No.3 nihilistic potential lies in its capacity to interact with the idea of the artist as creator, the concept of the handmade, and go beyond the mere idea of colorism in painting, or the idea of synthetizing abstractionism. It questions the concept of abstraction when there’s nothing to abstract, altering the process of creating an artwork as a submission to abstracting forces.

Line Study stands as a victory over nothingness as it creates a new vocabulary, and on its way to consolidate it, constructs new tools to generate its grammar. It proposes the possibility of painting as automated creation, of artist as machine, and the relationship between artist, process and artwork as a dynamic form of collective production. One idealistic future, a future of nothingness, could foresee a moment when the machine takes over, as a form of artificial creative intelligence. Line Study postulates the possibility of artist as Nothingness.

--

The ubiquitous nature of Nothingness allows it to be manifested no only in the process of creation for a single body of work, but also it foments its capacity to be summoned through a diverse plethora of concrete forms. In this sense, Nothingness can be perceived everywhere, from a painting, to a video.

Product of an epistemological exodus, Nothingness arises whenever an underlying rhetorical apparatus is transformed into conceptual erasures consolidating voids that cannot be filled by any of the current discursive contents. Still a concept in a post-conceptual world, Nothingness also uses art as a grammar to deliver undecipherable messages; malleable codes that react with indifference to actual language and narratives. The work of Garcia Frankowski presents a universal grammar of Nothingness. Manifested in its multiplicity of conditions, this grammar takes the form of an ontological juxtaposition as nihilistic vocabulary. Its forms are not just devoid of specific meaning, but allow for self-generation of new cognitive structures able to inhabit the desert first visited by the Black Square.

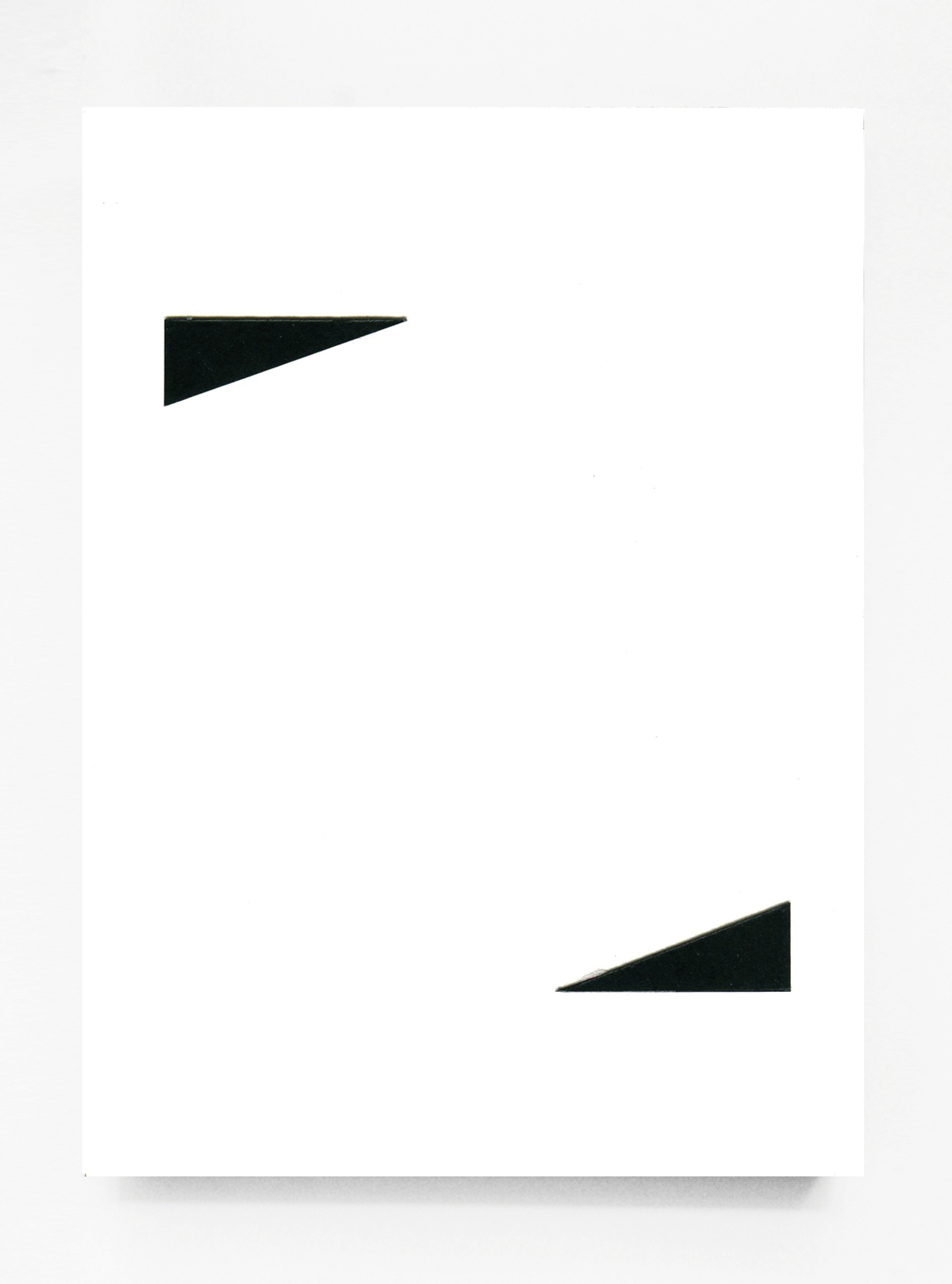

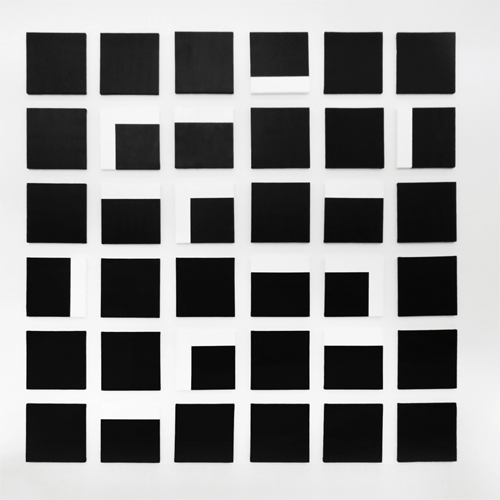

Painting and video are two of the vehicles used to cruise inside that meaning-less desert. On one hand, ‘Reconstructed Composition No.3’ devices an archetype of a monochromatic set of endless variations of compositional strategies created by assembling, and sewing, painted and cut geometric shapes. Lacking a narrative story or a pictorial reference, the reconstructed composition, reconstructs also the possibilities of art as an epistemological device, offering pure form as post-conceptual grammar. A painting made out of other paintings, ‘Reconstructed Composition’ creates Nothingness by assembling fragments of nothingness inside an allegorical frame, like the one that outlined ‘Purse Snatch in Streetcar’. Reconstructed Composition, thus serves the same role of a nonsensical phrase outlined and framed as it has embedded all the meaning it needs to deliver its ‘non-message’ by way of its grammar of nothingness.

With unfolding found footage as disjunctive narrative, the installation Rhetorical Reconstruction presents two video collages as compositional nothingness. Duchamp endlessly repeating “but I don’t mind at all, I don’t care” creates an absurdist acoustic background environment in which images of Hugo Ball, Duchamp, Mayakovski and found footage of one of NASA’s space projects speculate on the possibility of cosmic discovery as driven by the same creative forces that pushed the avant-garde to not only look for the possibility of Nothingness, but to declare a victory over it. After all, aren’t the space and the universe the ultimate nothingness? Isn’t space exploration venturing in the same nothingness inhabited by the discontinuous poem of absurdism?

Compositional Video and painting play with the notion of reconstruction, of disjoined surfaces and events, images, pieces attached to each other by external forces that respond to a metaphysical motive, to an ultimate, sublime manifesto of the assembling, and dismounting possibilities of nothingness.

--

The Manifesto as metaphysical motive acts upon the notion of transcendence of the artwork. In order for the artwork to push the project of Nothingness, it must rebel against the object of ‘something’ that would be the depiction of the world. On this notion Pavel Kiselev’s presents a work reflecting on the notion of contemporaneity and the possibility of nothingness today, in a period of oversaturation of information, in an age of commonplace prophecies and urgent messages.

Exploring uncertain terrains opened by previous experiments of layering and stratification, ‘The New Message’ ventures inside nothingness as a black hole inside a universe impossible to navigate with clarity with current tools and knowledge. This absolute nothingness pulls the viewer inside its vortex, a black nothing that absorbs external forces challenging the fact that now, every two days humankind produces as much information as it was ever produced until the fin d’ siècle. The New Message creates the possibility of a new starting point for everything. It proposes a new Victory Over Nothingness based on the capacity of the artist to create a vocabulary able to cancel all the atmospheric noise produced by oversaturation of images, by the production and distribution of contents that are thrown to the world at exacerbating speed and in overwhelming quantities.

The content of the artwork is freed from external forces with a form of radical indifference, creating with its own energy, the atmospheric gravity of the territorialization of nothingness.

The New Message creates a new space to legitimize the concept of Nothingness as a challenge to the omnipresent ‘everything’ of information, language, and messages. It creates a space for articulation as territory against the deterritorialization of virtual space and ever expanding domains of external interests dominated by socio-cultural, political and economic interests. When an artwork reaches the state of Nothingness it does so by defying every platform that proposes ‘something’, however abstract this ‘something’ may be.

--

The Internet is one of these domains that offer the permanent possibility of interacting with something happening somewhere. A channel for mass diffusion, it provides every moment with more information, more images, more content than ever before. Nothingness now is presented with challenges that didn’t existed a hundred years ago. Black Square and readymade are still transcendental today, although absorbed inside the milieu of the materialistic dialectical apparatus. Not just the work is submitted to external forces that corrode their nihilistic strength, Malevich and Duchamp as pictorial icons are thrown into virtual space incessantly, summoning their image and making the idea of Nothingness into its opposite. We are witnessing a banalization of the image of Nothingness.

As Boris Groys affirms, it is through the Internet that conceptual art today has become a mass cultural practice. And while it can be argued that the visual grammar of a website is not too different from the grammar of installation space, it is still the challenge of the artist to conceive what power does he or she has by approaching the possibility of nothingness.

Contemporary means of communication offer global populations new ways to consume art. In a Post conceptualist world, in a world of Nothingness a new relationship between the space of extreme proliferation of images and the controlled environment of the institutionalized space of exhibition is possible. Nothingness is a conceptual adhesive that can bring extreme opposites inside a constructed conceptual void. Aoto Oouchi (a computer generated name) proposes a merger between these two realities. Nothingness exists in the realm where the nothingness of the virtual and the physical become absorbed by a regime of philosophical nihilism. The image is created as nothingness, with nothingness as a reference, and nothingness as a goal. Black Square spins out of control over images of the commonplace as to highlight the varying speeds, conditions and characteristics of two dimensions that ate subjected to a complete different set of rules and conditions. The static image of nothingness is altered by a never-ending sequence of loops and spins, of reloads and refreshes (to use internet language), highlighting the abyss that separates something to nothingness, this and that.

The infrastructure that supports accepted conceptions of aesthetics, and taste, of the production and consumption of art is tackled by a form of conceptualism that questions the foundations of the concept itself. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit postulates how self-consciousness arises at the moment of mortal danger. In a world where nothingness reigns supreme, in a world without ‘spirit’, the self-consciousness of the artwork arises when confronted with the endless void of nothingness.

Black Square and Readymade are the hammers that torn down the walls of preconceived discourses, of understandable narratives. After a transition space was created by imploding obstructing structures a set of Machinistic paintings, juxtaposing compositions, absorbing vortexes and virtual/physical palimpsests could roam free on a world without walls. With the walls torn down, all is left is to enunciate the ultimate victory. To declare a victory over nothingness.

Text published on the occasion of A Victory Over Nothingness: Purse Snatch in Streetcar and Other Post Fevralist Absurdities

MANIFESTO ON NOTHINGNESS

Garcia Frankowski

Nothingness has the virtue of surviving through any battle. Modern warfare not in the format of drones or cyber espionage, but in the polarization of a materialist dialectic, absorbs everything into its insatiable vortex. Nothingness is the ungraspable matter that is left after everything has been consumed.

Nothingness is that dessert of hard, irreverent edges. Nothingness waits indifferent at the other side of a door opened a hundred years ago in an attempt to reach the ultimate sublime. In a world plagued with opportunistic ideologies and temporary systems, passing regimes and totalitarian dogmas, Nothingness remains immutable.

This Nothingness looks past the dialectical relationship between the existence-driven non-consciousness of objects in their being-in-themselves state and self-conscious subjects that through being-for-themselves become aware of their existence in their deprivation of autonomy from a world consisting of predetermined systems and objectivized matter. When rationale and logic, when the visceral and the subconscious are transformed in the grammar of commoditized matter, Nothingness speaks an unintelligible language. Nothingness looks past structures of reason, however pure, dialectical or cynical they might claim to be. Nothingness has no method and denies any praxis.

Confronted with an ever-expanding black hole that absorbs whatever manifestation of everyday life, Nothingness is freed by its inherent lack of light. In a world without qualities, Nothingness is enlightenment as self-preserving darkness. Absolute Nothingness strives in absolute obscurity. Nothingness exists in the words of this manifesto and in the basic manifestations of its formal articulations. Its processes and actions, shapes and outlets are the inherent, universal language of silence. Without uttering a word, Nothingness communicates undecipherable dictums.

Operating as a critical project since the creation of the Readymade, and as a post-critical axiom since the first Black Square, Nothingness inhabits an interstitial space invisible to the shortsightedness of current aesthetic-political values. Nothingness is the ultimate goal of its own project. Nothingness is self-sufficient, absolute.

However clear its cartographic characteristics, and its intellectual makeup, Nothingness is not a doctrine, or a regime, or a dogma. Nothingness obliterates any stereotype, preconception, and expectation. It implodes any structure. It destroys the crushing weight of paraphernalia of superfluous authenticity, be it of the superficial metaphysics of awareness and responsibility, or the hypocritical forms of empathic aesthetics and altruism. Nothingness refuses to carry the fictional weight that has been thrown to in order justify volatile relevance, fluctuating value, and oscillating legitimacy. Nothingness is all that is left after humankind has been sequestered by its self- imposed conditions. Nothingness is pure freedom; Art as Nothingness.

Text published on the occasion of A Victory Over Nothingness: Purse Snatch in Streetcar and Other Post Fevralist Absurdities

SUPERFOLDING

Garcia Frankowski

The Baroque does not refer to an essence, but rather to an operative function, to a characteristic. It endlessly creates folds. It does not invent the thing: there are all folds that come from the Orient—Greek, Roma, Romanesque, Gothic, Classical folds…But it twists and turns the folds, takes them to infinity, fold upon fold, fold after fold.

–Gilles Deleuze, The Fold

The Superfold is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. As with the fold, with its twists and turns, coils and bents, its performative (dis)continuality has the capacity to connect on a single surface a plethora of multiplicities. Either metaphysical or material, in the form of a textile labyrinth or as the endless projection of images, the fold can outline topographical cartographies of rizhomatic relations as connective tissue of history and visual information. The artwork and the work of art (as in the production of the artwork) act as both as signifier and signified, codifiers and decoders of processes that are then revealed as a network of connections of multiplicities and episodes, as extensions of surfaces and cognitive relations.

In its superlative function, the Superfold explores surface extension, albeit in all directions. The Superfold is the folds magnified. It is simultaneously folded as sensuous device, as time-space machine, as performative recording, as historico-epistemological coiling, as philosophical cloth. The Superfold extends in different forms, from the folding cloth over furniture of Meng Zhigang, to the hypothetical bottom layer of naked female skin potentially covered by sensuous clothes conceived by Vega Zaishi Wang, the washed-out covers and advertising pages of fashion magazines of Ren Zhitian, the machinist images projected into space into a cache of assemblages of enunciation of Ophelia S. Chan, and the Deleuzean dialectical historic-epistemological folds of the baroque dresses worn by a headless woman in Marianna Ignataki’s work.

Folding in and out of itself, the exhibition creates an extended territory that bends and turns, twists and loops far beyond the contained reach of the physical limits of the gallery, folding into an endless Superfold.

Fold as Sensuous Device

The work of Vega Zaishi Wang deals with one of the most fundamental folding strategies: the ontological fold as sensuous device. Clothing, which takes form within the socio-cultural apparatus in the realm of fashion, deals with several simultaneous folds. The fold of being is defined by a carefully conceptualized series of garments meant to be worn in order to create an extension of the self while developing a collective formulation of being (as in being in the world). If being is defined by the spaces we inhabit whether cultural, geopolitical, philosophical, psychological), clothing and fashion at large is potentially the most intimate of those spaces, where in its tangible manifestation or in its more underlying societal role. Every cut, every texture, fabric selection, color and design decision deals with a multiplicity of layers that bend and materialize as folds with the potential of extending towards the user as it becomes seduced by the experience of wearing it or to the viewer who is attracted to the sensuousness of the garment as a visual device. The body is extended by additional folds that form a continuous layer and an expansion of itself.

Fold as time-space machine

Ophelia S. Chan deals with the fold as a dual machine working with both time and space. Two metal stands hold a monitor and a mirror respectively. Behind the mirror a wireless camera captures images of unsuspecting viewers that look at their reflection without noticing that their image is being projected in the monitor’s screen. This cache or visual loop creates an iteration of the fold as machinist dialectic, as stream between time and space, author and user become embedded in this device of assemblages of enunciation. The fold here works in all directions and manifests itself in all the elopements whether virtual of physical: from the objects (monitor and mirror), to the space that contains them (the gallery and the virtual vacuum of image transposition), to the time consumed to capture and project the images and in the viewer captured in these images that make him into an involuntary performer and as a fundamental part of the artwork that is only completed one the fold extends from time to space by means of the body.

Fold as performative recording

Superfold presents two series of works by Ren Zhitian. ‘Gauze Curtains’ are two collages made out of a series of covers and advertising pages of fashion magazines that have been washed down until being turned into abstract compositions of pastel colours and barely discernible silhouettes of female figures. A commentary of the superficial character of these types of paraphernalia, his works on mix media are also a fold of process and visual information. The found images are transformed into something new without completely discarding its history. What is left is composition as performative recording, as these new images carry the actions that were executed upon them, and while creating new visual forms they still carry the meaning of a previous life not so disconnected to the aesthetics of the surface. These two pieces are accompanied by an artifact that although possesses completely contrasting visual characteristics still carry the same function of fold as performative recording. ‘Skin’ consists of an oversized sheet of paper hung from the wall. Not like any piece of paper, Skin displays the visual evidence of a yearlong performance where the artist danced and stomped on its surface, creating a piece that carries the physical history of its past while presenting the dialectic of form and action that is also part of his two ‘Gauze Curtain’ pieces. The ritualistic violence intrinsic in acts of stomping and dancing or of continually washing down until the point of deformation make the these pieces unified by a fold of action and performance, by a coil that bends in the direction of physical activity and ends as visual recording.

Fold as historic-epistemological coiling

By reworking François Boucher ‘La Toilette Intime’ or ‘Une femme qui pisse’ (c. 1760’s) Marianna Ignataki confronts us with refrerences of an epoch that Gilles Deleuze affirms ‘does not refer to an essence, but rather to an operative, function, to a characteristic’, a characteristic that ‘endlessly creates folds’, that while does not ‘invent the thing’ it ‘takes them (Orient, Greek, Roman, Romanesque, Gothic, classical, and we may add, modern, contemporary and so of and so on) to infinity, fold upon fold, fold after fold.’ By bringing a Baroque painting back to life is not the Baroque what is brought back as an event, but the events that the baroque summoned and in this case the fold of the folding fold. If matter (historical, visual) was amassed into these coiling folds, the amassing matter of that fold is the Superfold. The folds in Ignataki’s ‘Adore me’ coil upon history and medium, towards representation and message. By reworking a work product of historic-epistemological coiling the fold is revealed, not only on the suggestiveness of the pastel colours, smeared gouache and color pencil tones, but on the varying surfaces of the baroque topographies and the endless folding of the contemporary also as more than an essence, but as an accumulation of infinite converging events, mediums, strategies and devices. ‘Adore Me’ contextualizes the fold from a Deleuzean point of view, unfolding the baroqueness not only in its image but on its operative function as well.

Fold as philosophical cloth

Following the path of his previous work series –hovering institutional buildings first followed by empty rooms—Meng Zhigang extends his philosophical questioning to smaller scale items. Obliterated from his paintings of architectural spaces, furniture appears to pay closer attention to the meaning left unearthed from his Taoist empty spaces. However, as with the ethereal pictures of containment, his painting of furniture throw a new layer of philosophical folding on his own questions that were left unanswered by objects of larger scale. By depicting clothes that disguise the furniture, a new fold is revealed, that of the guessing sight that imagines what lies under the fabric. Like a mask, the blanket covers what was previously removed from his empty-rooms-as-self-portrait, and extend the philosophical mystery by depicting coiling and undulating surfaces that connect with his inner self and with the works that preceded by means of a fold that wraps endlessly endlessly. Furniture covered by philosophical cloths. Philosophical cloth as Superfold.

FOLDING STORY